Summary: Process Chain with FFF

The summary could be divided into the assembly vs. decompose, consolidate, and process chain. We are going into more detail when necessary.

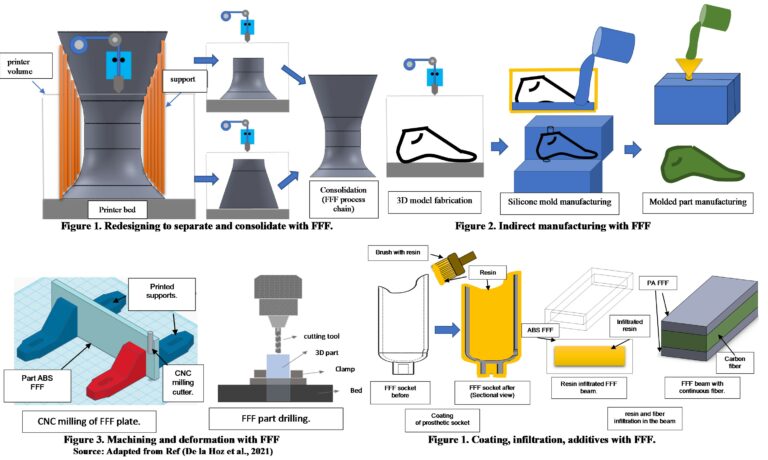

Assembly vs. Consolidation/Decomposition

There are several general possibilities:

- consolidating or merging parts

- decomposing or separating parts, hybrid, or combination

- modifying the shape and incorporating unique features

- doing nothing (on a pre-existing design)

Each option has its advantages and disadvantages; the possibilities and causes by type are listed below.

Consolidation may be due to the following reasons:

- Reducing part count and assembly times.

- It could include the fusion of multiple materials in different visible phases to take advantage of the specific properties of these or to counteract disadvantages, for example, support or maximum print volume.

Decomposition may be due to the following reasons:

- Maintenance and replacement of parts due to wear or damage without compromising the entire system.

- Replacement to comply with modular, customization, or individualization functions that favor or detract from production and customer interaction.

- It can be decomposed to complement the weakness of some parts in a specific area by incorporating another part of a different, more resistant material.

- Capitalize on the advantages and counteract the limitations of the manufacturing process, including using parts of the same material but with different manufacturing parameters.

- Manufacture parts of different materials but with the same process, parts of the same processes and materials but different internal structure and composition, or parts of different materials and processes.

The combination or hybrid may be due to the following reasons:

- To decompose into parts, relocate, redesign, and consolidate, considering the function, printing orientation, and limitations.

- Manufacturing parts are to be separated during the initial fabrication. However, they are to be consolidated in the final stage to gain cost or time advantages or improve the final product’s performance.

Modify Shape and Incorporate Special Features:

- Incorporate features such as press-fit joints to facilitate assembly.

- Modify the shape of a joint to improve performance or counteract limitations (from seals) or facilitate the use of additional consolidation processes (hot air welding, use of quick-set adhesive, screws).

Doing nothing may have consequences on maintenance, assembly times, or overall performance but does not incur additional design time costs, which is implied in the above cases.

Once a decision has been made, a series of other specific aspects come into play to be considered in the case, for example:

- If a decomposed design is considered, you can manufacture it all at once or in parts, with consequences that entail the assembly, mechanical strength, tolerances, or the speed of production if other processes or materials are considered.

- In the case of consolidation, function control based on the internal structure in different zones implies topological or cellular structure design and optimization.

- In the case of pressurized joints, the constraint associated with the expected life and load cycles before failure depends on the manufacturing orientation.

In general, it is recommended to keep an open mind to the possibilities:

- Not just one process could be several, nor just one material could be several.

- Not just one part could be several.

- Not just consolidate and decompose; it could be both simultaneously.

- It could be just changing the form.

- Evaluate the consequences in each case and make decisions based on the requirements pursued.

Process Chain

Additive manufacturing produces complex shapes without relative cost and time increases. Everything is produced using a single 3D printer, additively without waste, with a minimum amount of personnel and tooling. In some ways, additive manufacturing is disconnected from conventional manufacturing.

However, Additive manufacturing has inherent limitations:

- Extended production times

- Low production rates

- Anisotropy

- Relatively high tolerances compared to conventional processes.

- High surface roughness

- Limited material variety per process

- Reduced mechanical strength compared to conventional manufacturing.

- Challenges with biocompatibility and sterility in medical applications

- Stringent tolerances at small scales

- Requirement for support structures for specific geometries

- Attention needed for sharp radii and corners.

- Restrictions on minimum allowable wall thicknesses and features

- Part volume confined to printer chamber size.

Some of these disadvantages can be mitigated by Careful selection of process parameters, application of design rules, optimization of planning and generation of manufacturing routes, and simulation and optimization of the final part, among others.

The truth is that all the above requires more time for planning and designing the part and process, and production can be affected negatively or positively depending on whether what is pursued is to improve the performance or characteristics of the part or production. For example:

It is recommended to reduce the layer height and achieve better tolerances in cylindrical holes; it is recommended to orient the part so that these cylinders are vertical. However, the first measure increases the number of layers and, therefore, the manufacturing times and the second will increase the times if the length of the cylinder is greater than the diameter. In this case, production has been sacrificed to improve the performance or qualities of the part, which impacts costs and lead times.

There is another way to welcome or embrace the limitations of the specific additive process to take advantage of them and let other conventional processes with better performance when it comes to achieving specific final characteristics be the ones to finish the job, giving the part properties superior to the original additive process, and therefore breaking the limits of the additive process or at least displacing this barrier by reconnecting additive manufacturing with conventional manufacturing. For example:

In the case above, to improve roughness and tolerances, one can choose the (coarse) layer height and manufacturing orientation that reduce additive manufacturing times. This will produce parts quickly but with poor finish and tolerances. However, to achieve the goals of tolerances and roughness, post-printing machining processes, such as drilling or milling, are used to ensure both properties, although this involves additional resources.

As in assembly, in general, it is recommended to keep an open mind to the possibilities, and in addition to the final assembly, suggestions are added:

- Not just one process at the end; it can be several, not at the end, but before or during the process.

- It does not have to be direct manufacturing with FFF; the AM can be a secondary process to support a primary process.