Medications (MED)

Next, there are some guidelines for medical and individualized cases with their coding, obtained after analyzing the respective references, and grouped by case study and common trends, highlighting in bold the competitive advantages that can become innovations.

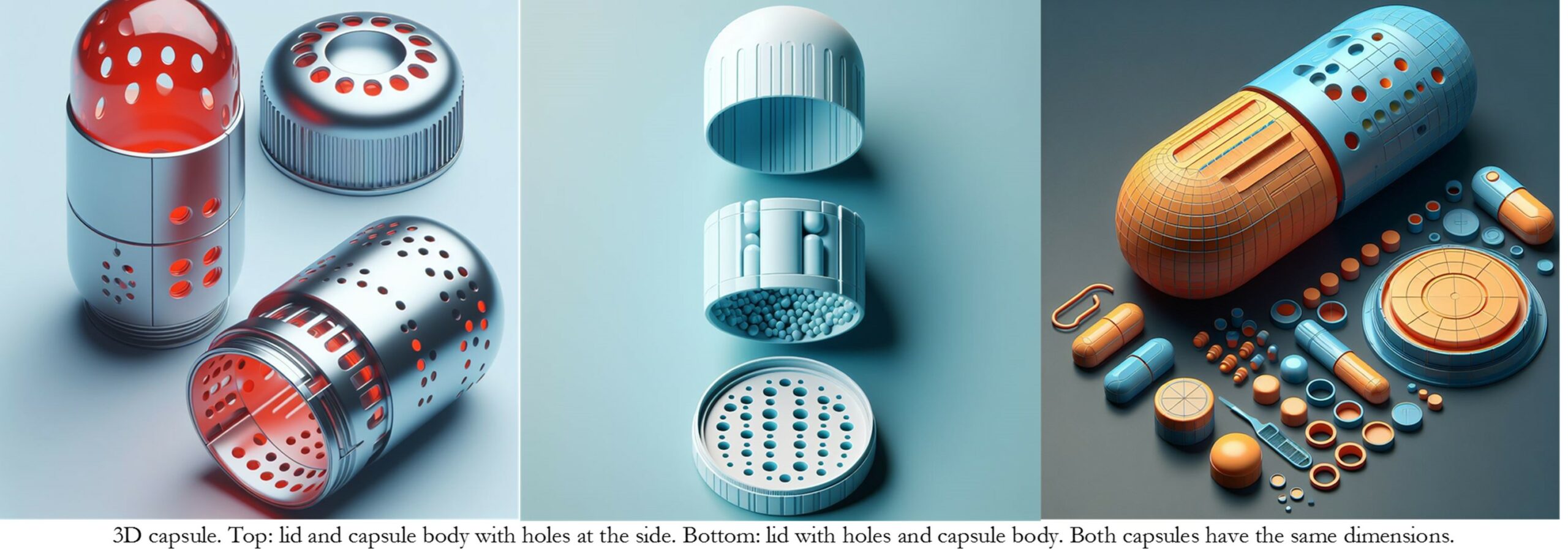

MED-01. Holes of different sizes (1.5 and 2 mm) and quantities (4, 5, 8, 12) and positions (side vs. top and bottom) should be incorporated into a rigid, biodegradable capsule to control the rate of drug release [1].

MED-02. The following biocompatible materials should be used (studies pending): ABS, PLA, polyvinyl alcohol, ethyl vinyl acetate, and polycaprolactone [1].

MED-03. A thin layer of kerosene film covers the small gaps between the lid and the scaffold body to ensure drug release into the medium only occurs through the designed holes [1].

MED-04. The scaffold lid has a 12 to 14-mm diameter and fits exactly into the scaffold body. The cap can be 1.5 mm thick. The capsule can have a diameter of 17 mm, a wall thickness of 1 mm, and a base thickness of 1.5 mm [1].

MED-05. Manufacture drugs using FFF/FDM in the following ways:

Manufacture Encapsulation.

- Manufacture via 3D printing the encapsulation, providing holes in the appropriate quantity, position, and size, or using water-soluble materials with wall thicknesses and specific patterns previously characterized to control the release rate. Subsequently, pack the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) inside these printed encapsulations [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

Load filament with API by HME.

- Previously manufacture the filament combining the API in high percentage with the polymer through hot melt extrusion (HME) [6].

- Extrusion can be performed using the Single Screw Extruder, which is cost-effective, compact, and easy to maintain, and the Twin Screw Extruder, which is capable of providing better mixing and output [6].

- Subsequently print the drug with the filament loaded with the API considering different:

- Size or volume [7].

- API load percentage, polymer, and others [7].

- External shape.

- Height, diameter, or dimensions [7].

- Printing fill percentages [8].

- Layer thickness [7], [8].

- Internal patterns: Honeycomb, Sandwich, capsule, mesh, concentric, among others [7], [9].

- Relate area/volumes [8].

- Wall thicknesses

- Previously characterized to regulate the release rate and according to the characteristics of the patient or to achieve additional functions such as identification and traceability.

Load filament with API by dissolution, impregnation, or absorption.

- Immerse filament in a solution with the API and load it in small percentages by dissolution [6].

- It may be necessary to dry before printing to remove the solution adhered to the surface.

- Subsequently print the drug with filament loaded by dissolution, taking into account the API percentage to manufacture sufficient volume of medication according to specific medication [6].

- The percentage of drug weight loaded can be calculated considering the initial and final weight of the polymer after drug loading [6].

- The load percentage is generally lower compared to other techniques.

- Not all polymers can be easily loaded using this technique [6].

- You can print the drug or pill first before immersing it in the API solution, achieving faster release rates than the counterpart of impregnated filament [6].

- You can combine both methods, that is, first impregnate the filament with the API and after manufacturing the pill, impregnate it with a different API. Slower release rates are achieved with this method [6].

- It is an economical but slow method to implement.

Load drug with API by coating

- For oral tablets, incorporate an enteric coating to avoid gastric conditions and release the drug in intestinal locations [6].

- Use transdermal patches (e.g., a PEG micro-needle patch) coated with the API to later release the drug into the patient when applied to the skin [6].

Implant or scaffolding.

- Print implant or scaffolds and immerse or coat them in a solution with the API to subsequently implant it in the specific tissue or particular area of the patient [6].

Other forms such as the manufacture of molds to mold the drug [6], [10], or sublimation [11] exist.

MED-06. Consider the following recommendations concerning the drug formulation in terms of Carrier, API, and additives:

Carriers.

- Cellulose derivatives (HPMC, HPC, EC, HPMCAS): Used to produce gastro-retentive floating devices with zero-order release by varying the air chamber to obtain different release times. Also used in combination with other pharmaceutical polymers that are difficult to feed, to enable processing on FDM/FFF apparatus [12].

- Ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA): EVA with a high VA content is too flexible for successful printing. EVAs are biocompatible and not water-soluble, making them ideal polymeric carriers for the development of sustained-release pharmaceutical forms, such as implants [12].

- Kollicoat IR: Freely water-soluble, therefore the dosage forms produced exhibit immediate release behavior. The raw material can be easily printed and satisfactory prints have been recorded with solid loads of up to 40% [12].

- Polycaprolactone (PCL): A biocompatible and biodegradable polyester. It is easily printable and has been used in many studies in combination with drugs such as indomethacin or theophylline. Drug release occurs by diffusion, making it a suitable carrier for sustained release applications like intrauterine devices [12].

- Polyethylene oxide (PEO or PEG): Added to a formulation to act as plasticizers or pore formers to enable printing. It has been combined with PCL or cellulose derivatives. The resulting release behavior could be zero-order or immediate, depending on the molecular weight and tablet design.

- Polylactic acid (PLA): Biocompatible and biodegradable, commercially available. Drug dissolution generally occurs by diffusion from the polymeric matrix. It has been used to produce dosage forms that were subsequently loaded with drugs using the impregnation method [12] and also as capsules [1].

- Polymethylmethacrylates, Polyurethanes (PU and TPU): Used to produce sustained-release implants. Currently, polyurethanes are not approved for oral administration, although various studies have highlighted their compatibility with the 3D printing FDM technique and their potential in the production of solid oral dosage forms [12].

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA): The polymer is hygroscopic (requires proper storage to avoid stability issues of the resulting filaments) and commercial, is water-soluble, and therefore used to formulate immediate-release tablets. The resulting filament is printable but generally brittle when combined with higher drug crystalline contents (>20%), requiring plasticizers to enable processing. Drug loading is often achieved using passive diffusion [12], but also for manufacturing capsules [1], or by HME [3].

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP): As these polymers are freely soluble in water, they are designed for immediate release dosage forms. Additionally, it is hygroscopic and requires proper storage.

- Soluplus: Due to its amphiphilic behavior, it is capable of solubilizing poorly soluble drugs to increase their bioavailability while showing immediate release behavior. Soluplus is too brittle to allow direct printing and requires the addition of a plasticizer.

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API).

- Selection of Polymer and Process: The API determines the carrier polymer and processing conditions to minimize degradation [12].

- Anhydrous Processes: HME and FDM avoid hydrolytic degradation of the API as they are water-free techniques [12].

- Thermosensitive Drugs: Heat-sensitive drugs may be difficult to process, although the appropriate choice of polymers can facilitate their handling [12].

- Formulation Stability: The stability and processability depend on whether the API is dissolved or dispersed, with a preference for dispersions for stability [12].

- Drug-Polymer Miscibility: Hansen solubility parameters predict compatibility between drugs and polymers, essential for designing effective release systems [12].

- Challenges in 3D Printing: Crystalline drugs can complicate 3D printing due to mechanical problems and nozzle clogging [12].

- Impact of Crystalline Drugs: High concentrations of crystalline drugs can affect the morphology and quality of the product, although techniques such as milling can help [12].

- Plasticization by API: Some APIs can act as plasticizers, improving the handling and formulation of the polymer [12].

Process Additives.

- Plasticizer: Reduce the extrusion temperature and improve the elasticity of the filament. Examples: triethyl citrate, glycerin, PEG [12].

- Dissolution Modifier: Accelerate the disintegration of tablets and adjust drug release. Examples of disintegrants: starch, crospovidone. Materials for channels: PEG, mannitol [12].

- Inert Filler: Stabilize the flow and improve feeding in extrusion. Examples: talc for flow stabilization, tricalcium phosphate for consistent flow [12].

- Lubricant: Facilitate the extrusion of powders with poor flow and prevent adhesions. Examples: colloidal silica, magnesium stearate [12].

- Special Excipient: Improve the handling of the filament and protect the drug. Examples: castor oil for lubrication, titanium dioxide for UV protection [12].

MED-07. Consider the following experimentally tested combinations of API with different forms of application and release/type of disease to treat/carrier polymer and process additives/manufacturing process:

Tablets and oral forms

- Cardiovascular disease

- Dipyridamole, theophylline: Immediate release/cardiovascular disease/PVP, talc/HME [13], [14].

- Warfarin: Ovoid oral tablets/cardiovascular disease/TEC, TCP, Eudragit L/HME [6].

- Theophylline: Radiator shape+ Sustained, rapid release/cardiovascular disease/PEO, PEG/HME [6].

- Theophylline, budesonide, diclofenac sodium: Core-shell oral tablet + enteric, delayed release/cardiovascular disease, renal, arthritis/Eudragit L (enteric coating) + PVP (core)/HME [13], [15].

- 5-ASA, captopril, theophylline, prednisolone: Immediate release/cardiovascular disease/Eudragit EPO, microcrystalline cellulose, talc, tricalcium phosphate in various proportions/HME [13], [16].

- Prednisolone: Extended, sustained, controlled release/cardiovascular disease/PVA/dissolution, impregnation, absorption [13].

- 5-ASA/4-ASA: Extended, sustained, controlled release/cardiovascular diseases/PVA/dissolution, impregnation, absorption [13].

- Lisinopril Dihydrate, Indapamide, Rosuvastatin Calcium, Amlodipine Besylate: Oral polypill/cardiovascular disease/PVA, Sorbitol, titanium dioxide (TiO2)/HME [6].

- Theophylline, Dipyridamole: Immediate release/cardiovascular disease/PVP, TEC/HME [6].

- Gastrointestinal or colon diseases.

- Budesonide: Oral capsule + sustained, controlled release/gastrointestinal or colon disease/PVA/HME [13], [17].

- Domperidone: Floating oral tablet/gastrointestinal disease/HPC/HME [13].

- Neurological or psychiatric diseases

- Carbamazepine: Oral capsule + sustained, controlled release/neurological or psychiatric disease/ABS/capsule manufactured with FFF + manual API packaging [13].

- Carvedilol, haloperidol: Rapid release/cardiovascular, psychiatric disease/PVA/HME [6].

- Aripiprazole: Orodispersible film/Mental disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Tourette syndrome, and irritability in autism)/PVA [18].

- Cannabidiol: Orodispersible film/Mental disorders and pain/PEO [18].

- Diabetes

- Glipizide: Polypill/Type 2 diabetes/PVA/HME [6].

- Metformin Hydrochloride: Diabetes/PVA/dissolution, impregnation, absorption [6].

- Pain, fever, and inflammation

- Ibuprofen: Tablet with variable internal density percentage + extended, sustained, controlled release/pain, fever, inflammation/PVA, HPMC, Ethyl Cellulose/HME [6], [19].

- Paracetamol: Capsule with QR code/pain, fever, inflammation/L-HPC, Mannitol, magnesium stearate/HME [20], [6].

- Paracetamol: Enteric, delayed release/pain, fever, inflammation/HPMCAS, magnesium stearate, methylparaben/HME [13].

- Acetaminophen: Sustained, controlled release/pain, fever, inflammation/HPC, Eudragit L100, HPMC/HME [13].

- Paracetamol: Pain, fever, inflammation/PVA/HME [6].

- Paracetamol/caffeine: Pain, fever, inflammation/PVA/HME [6].

- Paracetamol, ibuprofen: Orodispersible film/pain, fever, inflammation/PEO, PVA [18].

- Diclofenac sodium: Mucoadhesive oral film/rheumatoid arthritis/PVA [18].

Implants and/or endoprostheses/Stents

- Methylene blue, sodium ibuprofen, ibuprofen acid: Sustained release/pain, fever, inflammation/PLA, PVA/Dipping coating [6].

- Tetracycline: Release through orthopedic liner/joint bacterial infections/PLA/dissolution, impregnation, absorption [6].

- Penicillin: Nasal endoprosthesis/bacterial infections/PVP/dissolution, impregnation, absorption [6].

- Bevacizumab + dexamethasone: Ocular implant (coaxial bar) + sustained release at two different rates of the two APIs/retinal vascular disease/PCL + Alginate Hydrogel/HME+FFF/FDM coaxial [21], [22].

- Nialamide and sodium salt of inositol phosphate: Endoprosthesis or Stent + sustained release/patients with coronary intervention/PCL+ graphene nanoplatelet [22].

- 5-fluorouracil: Esophageal Stent or Endoprosthesis/Malignant tissues in the esophagus/ChronoSil AL 80A 5% silicone [22].

- Triamterene: Tracheal Stent or Endoprosthesis/Diuretic administration in the trachea to treat edema/PLGA [22].

Scaffolding

- Diseases in bones and skin

- Prednisolone, Dexamethasone: Inflammation and bone healing/PLA/dissolution, impregnation, absorption of filament before printing and after manufacturing by scaffold printing [6].

- Vancomycin: Bone infection/PCL, PDA, PLGA/dissolution, impregnation, absorption of scaffold [6], [23].

- Gentamicin sulfate, Tobramycin, Nitrofurantoin: Loaded filaments/Osteomyelitis/PLA, PMMA/HME [6], [24].

- Iodine: Meshes and endoprostheses/Skin infections/PVA/Sublimation [6].

- Cefazolin: Bacterial infection of the skin and bones/PCL/HME [6].

- Bone morphogenetic protein: Bio-inspired scaffold/bone regeneration/PLA/HME [6].

- Bone morphogenetic protein: Local sustained release/bone regeneration/PLA/dissolution, impregnation, absorption [6].

Rectal/vaginal delivery

- Gynecological diseases

- Progesterone: Molds for suppositories + sustained release/gynecological issues/PVA/direct drug administration [6], [10].

- Progesterone: Molds for suppositories + sustained release/gynecological issues/PEG4000, PLA, PVA, Tween80/HME [6].

- Estrogen, Progesterone: Biodegradable implant + hormonal release/gynecological issues/PCL/HME [6].

- Soft human tissue, PMME: Vaginal cylindrical applicator/endometrial cancer/ULTEM 9085/direct drug administration [6].

- Pain, fever, and inflammation

- Indomethacin: T-shaped intrauterine system/pain, fever, inflammation/PCL/HME [6].

- Indomethacin: Intrauterine system and subcutaneous rod/pain, fever, inflammation/EVA/HME [6].

- Artesunate: Rectal suppository/malaria/PVA/mixed with PEG [6].

Transdermal patch/mesh

- Copper sulfate, zinc oxide: Dressing for skin infections/PCL/HME [6], [25].

- Estrogen, Progesterone: Mesh + hormonal release/gynecological issues/PCL/HME [6].

- Gentamicin: Hernia repair meshes/bacterial infection/PLA/HME [6].

Catheters

- Gentamicin: Drug-releasing catheters/dermatological diseases/PLA/HME [6].

- Tetracycline hydrochloride: Anti-infective dialysis catheter/infection/TPU/HME [6].

You can consult reviews on the topic of API combinations, application forms, carrier materials, additives, and processing methods in recent references from the last 5 years [25], [26], [27], [22], especially how composition, form, and processing can affect customization and release rate in oral administration APIs [28].

MED-08. Apply drugs using FFF/FDM in the following ways:

Customization

- Design and manufacture drugs in individualized doses and specific release rates depending on the disease, weight, age, pre-existing conditions, among other characteristics of the specific patient [12], [13], [29], [30].

Poly pills or oral mediums

- Print different layers of medication, with different filaments loaded with specific APIs. One layer of medication on top of another to treat specific symptoms for each layer, for example, 2 to 4 layers of different medications. Additionally, each layer can be designed based on the desired release rate by modifying the fill percentage, height, diameter, wall thickness, among other parameters to manage different release rates for each medication layer [12], [13], [29], [30].

- Manufacture capsules with multiple compartments, one for each API to be packaged, and to treat specific but complementary symptoms of a disease [29]. Also, use the compartments to release several pulses of the same medication in the form of doses. Additionally, each compartment can be designed to manage different release rates by the number of holes, position and size, or in the case of water-soluble material with the wall thickness and pattern of these [4], [5], [12], [29].

- Print different medications that then couple with specific shapes that facilitate this, for example, in the form of a pyramidal puzzle [12], [13], [29], [30].

- You can also manufacture and apply oro-dispersible and mucoadhesive buccal films [18].

Implant or scaffolding.

- Print implants or scaffolds and immerse or coat them in a solution with the API to subsequently implant it in the specific tissue or particular area of the patient [12], [13], [29], [30].

- Print filaments loaded with APIs previously for implanting or positioning endoprostheses or stents and release sustainably [21], [22].

Transdermal patches/meshes.

- Manufacture transdermal patches or surgical meshes to protect areas of infection or release hormones, through loading the API into the filament with HME [6], [12], [25].

- Manufacture micro-needles for transdermal applications by means of filaments loaded with drugs via HME, or by coating the micro-needles once 3D printed with a drug coating [6], [12], [30].

- The dimensions of the micro-needles in transdermal patches usually range from 0.025 to 2.0 mm in height, 0.05 to 0.25 mm in diameter at the base, and 0.001 to 0.025 mm at the tip [31], complicating manufacturing especially at the tip by the FFF/FDM technique, with successful cases reported for AM CLIP process [32]. To achieve sizes between 0.001 to 0.055 mm via FFF/FDM, a post-processing protocol can be applied by chemical etching to sharpen PLA needles with an alkaline solution (dissolution), prior to loading the drug onto the needles [33], [22].

Catheters

- Load medications via HME into catheters with the purpose of protecting against infections or releasing medication into the patient [6], [30].

Vaginal or rectal application

- Medications can be manufactured for the treatment of pain, inflammation, and fever or gynecological issues, through:

- Manufacture hydro-soluble molds of PVA to directly mold the medication or suppository [6], [10].

- Manufacture bars for direct application with ULTEM [6].

- Use implants for medication release in the form of T or rings, which were previously manufactured with filaments loaded with API via HME [6], [12].

MED-09. Apply the AM concept at different medical pharmacological areas such as neurological diseases, cancer, chronic kidney diseases, cardiovascular diseases, severe acute ulcerative colitis, pediatric patients, diabetes, supplements, antimicrobials. Specifically, and at a conceptual level, employ FFF/FDM in diseases [29]:

Cardiovascular diseases.

- Theophylline manufactured by HME (Hot Melt Extrusion) for asthma treatment [34].

- Lisinopril, rosuvastatin, amlodipine, and indapamide combined with PVA filament via HME in the form of a polypill for the treatment of hypertension [35].

- Atorvastatin calcium to reduce cholesterol levels and prevent cardiovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and angina pectoris, and amlodipine besylate to reduce blood pressure, combined each with filament via HME and forming a two-chamber pill [36].

- Polypills printed manufactured with a PLA capsule and channels or with a PVA capsule with multiple concentric walls of variable thickness to regulate the controlled release rate of medications targeted at specific pathophysiological factors such as hypertension or dyslipidemia [37].

Neurological diseases.

- Pramipexole with PVA and levodopa and benserazide with ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) via HME with immediate and sustained release to treat Parkinson’s disease [38].

Pediatric patients.

- Caffeine and propranolol hydrochloride for treating hypertension [39].

- Indomethacin via HME to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation [40].

Severe acute ulcerative colitis.

- Metronidazole surrounded by PLA for treating infections caused by Helicobacter pylori through the printing of an anti-tipover capsule and packaging of the active component (API). Optimize previously the release rate (8 h) based on the size of the drug release orifice, the height of the air compartment, and compression strength [41].

Diabetes.

- Metformin combined with Eudragit via HME to regulate blood sugar and glimepiride combined with PVA via HME to stimulate insulin production by the pancreas, both combined in a bilayer pill for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, with sustained and immediate release profiles respectively [42].

- Metformin HCL with PVA via solvent diffusion. Modify the geometry, the fill percentage of the print, the fill pattern, and the inclusion of cylindrical channels, to increase the surface-to-volume ratio and improve the release rate [43].

- Metformin with TPU via HME. A sustained delivery of 24 hours of high drug loads can be achieved from 60% to subtherapeutic levels [44].

- Nifedipine to treat hypertension, simvastatin to reduce blood lipids, and gliclazide to reduce blood sugar, intended to treat metabolic syndrome. The three active ingredients (APIs) combined each with PEG 4000, HPC, HPMCAS, and magnesium stearate via HME and then manufacturing a polypill by printing three different layers, one for each API, with a dual-release rate, i.e., rapid (simvastatin 6h) and sustained (the other two 24 h) [45].

Cancer.

- Doxorubicin used as an anthracycline antibiotic antitumor combined with chitosan/Nano-clay/β-TCP via immersion and coating of PCL bone tissue scaffolding manufactured in a 3D printer. The scaffold should be implanted in affected bone tissue, while allowing tissue growth releases drug that combats residual tumor [46], [47].

Antimicrobials.

- Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a green tea polyphenol combined with nano-hydroxyapatite (HA) to coat scaffolds of PCLA manufactured in a 3D printer, with the aim of promoting bone tissue growth. EGCG has excellent antimicrobial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), preventing its colonization in the implants [48].

- Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with acetone solution, used in the coating of ABS, eliminate a wide range of microbial strains. It achieves significant bacterial reduction in 4 hours for species such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and in 19 hours for Candida albicans. The AgNP-ABS maintains effective antibacterial activity for up to 8 cycles of use [49].

- Rifampicin and isoniazid for treating tuberculosis, combined each with succinate acetate and hydroxypropyl cellulose respectively via HME. Print a bi-layer drug, one for each API, with different release rates by optimizing the rate based on the percentage load of the API, the fill percentage of the print, and the number of print layers [50], [51].

Supplements.

- Caffeine to induce alertness and attention based on body weight, age, tolerance, and genetic polymorphism of the users. Package in a two-compartment capsule of pharmaceutical-grade HPC manufactured via HME before being printed. The release of two pulses of caffeine is consistent with the two chambers of the capsule and meets the established elemental, microbiological, and by-product specifications [2].

MED-10. Design medications with shapes and patterns that facilitate identification and traceability by the patient or anyone in the supply chain:

- For blind patients, include shapes and patterns according to Braille and moon alphabets that allow them to read and identify the pill, and the consumption schedules. Consider the mechanical resistance of the medication to ensure the integrity of the pattern and legibility [52], [53].

- For pediatric patients, include attractive shapes that invite consumption of the medication, such as animals, different geometric shapes, flavors, or fictional characters [9], [18], [53], [54].

- Implement QR code by 2D printing, after the medication has been printed through 3D filament loaded with API, in order to identify traceability including the patient’s name, the prescribing doctor, and the use of the medication [6], [20].

MED-11. Design medications to prevent misuse in forms other than those recommended, by incorporating additives or carriers that hinder those other uses.

- For example, in the case of opioid medications such as Tramadol Hydrochloride that must be ingested orally, prevent solvency or use in the form of aspiration or intravenously. HPC and PEO can be used as carriers and additives which provide resistance to alcohol and moderating features against abuse, and similarly, PVA has deterrent properties against misuse [53], [55].

MED-12. Design the medication using theoretical numerical models to predict its behavior [56]:

- Normally, the following are used for simulating conventional drug release:

- Molecular dynamics simulation (MD)

- Monte Carlo (MC)

- Finite element analysis (FEA)

- Computational fluid dynamics (CFD)

- Density functional theory (DFT)

- Machine learning or artificial intelligence (AI) through Machine Learning (ML) to control drug delivery systems.

- Dissipative particle dynamics (DPD).

- Among the applications in simulation of these techniques are:

- Drug solubility, permeability, and adsorption

- Drug release from delivery systems

- Design and optimization of drug delivery systems

- Prediction of drug toxicity and safety

- Personalized medicine.

- Examples of reported case studies:

- Drug delivery systems (DDS) based on liposomes, with applications in tumor elimination and cancer.

- DDS based on polymers.

- Nanoparticles and nanosheets for DDS

- Implantable DDS

- Peptide-based DDS (PDDSs), with applications in various disorders including cancer.

- Antigen-based DDS (DDSs), with applications in cancer and conditions where a body immune response is required.

MED-13. For AM, use ML in the following ways to design, model, and control drug delivery systems:

- Use M3DISEEN (AI program on the web) to optimize FDM/HME parameters in the development of pharmaceutical formulations and verify manufacturability. It requires introducing the drug or API, carrier polymer, and weight proportions, as well as process parameters such as extruder and printer brand, extrusion and printing speed, bed temperature of the printer, type of medication, shape, area, volume, pH. As a result, it qualitatively predicts the mechanical quality of the medication, the extrusion and printing temperature, provides the concept about the manufacturability of the product, and predicts the drug release rate [57], [58], [59], [60].

- In this way, 614 formulations from 145 materials including 7 drugs were generated [57], [58], [59].

- Furthermore, a total of 968 formulations from 114 articles were evaluated to predict the drug release rate in combination with M3DISEEN to predict manufacturability, achieving prediction of drug release times from a formulation with an average error of ±24.29 min and providing accuracy up to 93% for HME process values [60].

- Although it proposes optimal combinations from the early phases, the need to manually input data accurately can prolong and increase the cost of the process [59].

- Use rheological data and ML to predict and evaluate the performance of formulations that are printable and with the desired release profile [61].

MED-14. Experimentally characterize the release rate of 3D printed drugs based on:

- Geometric variations: area, volume, shape or shape ratios, height, width, depth, external diameter and height, shape ratios, wall thicknesses, patterns, number of compartments, size of holes, location of holes, size of holes, shape of holes.

- Composition of materials: carriers, API, additives.

- Type of manufacturing: HME, diffusion, coating, encapsulation, molding.

- Manufacturing processes and their parameters: Printer temperatures, bed and extruder or process parameters of diffusion/coating, layer height, fill percentage, internal patterns, orientation of manufacturing, number of top/bottom layers, number of side or perimeter layers, extrusion and printing speeds.

- Rheological parameters and others: Viscosity, roughness, pH.

In order to obtain regression models with which to predict and control the release percentage as a function of time [1], [2], [3], [7], [8], [28], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63].

MED-15. The drug load percentage depends among other things on the manufacturing process, for example:

- Loading by HME: 35% to 95% of the fraction of the weight of the carrier polymer or additive, i.e., API is 65% to 5% [3].

- Dissolution/absorption/impregnation: 94% and 97% of the fraction of the polymer carrier, i.e., API is 6% and 3% [3], [64].

- Molding, encapsulation: API at 100% [1], [6], [10]

Adjust accordingly the final size of the medication to achieve the required concentration or dose.

MED-16. Common characterizations required to evaluate the quality of medication manufactured by FDM include [12]:

- Mechanical Resilience

- Topography

- Solid State and Degradation

- Stability

- Porosity

- Dissolution Behavior

- Homogeneity of Distribution

- Specific Requirements: Specific properties are needed for dosage forms intended for non-oral applications. Additional tests by type of application include:

- Implants: Tests for biocompatibility and cell viability.

- Formulations for bacterial treatment: Tests to confirm antimicrobial efficacy.

- Mucoadhesive Formulations: Evaluation of their mucoadhesive properties through mechanical tests.

- Skin Patches: Need for bending resistance and pH compatibility with the skin.

- Pediatric Formulations: Tests for masking the taste of medications.

- Flexibility of 3D Printing: Enables the production of dosage forms directly at the site of need.

- Photosensitivity of Certain Medications: Requires special packaging to ensure the stability of the product.

- Sterilization and Aseptic Production: Necessary for certain products such as wound dressings before application.

MED-17. Characterizations of medications from a perspective of the type of characterizations for FDM, include [26]:

- Thermal techniques: TGA (thermogravimetric analysis), DSC (differential scanning calorimetry) to verify the solid state.

- Mechanical techniques: Resistance to crushing; friability or fragility to verify resistance to handling; tension; compression; three-point bending; indentation; interlaminar adhesion.

- Rheological techniques: flow test, capillary test, creep test, frequency sweep.

- Spectroscopic techniques: Near-infrared spectroscopy to measure concentration and distribution; Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy for interaction of components; Raman including mapping and confocal to determine the solid state and distribution.

- Dispersion and imaging techniques: Angular X-ray scattering, scanning electron microscopy, X-ray powder diffraction, small-angle neutron scattering, X-ray computed microtomography, pulsed terahertz imaging, time-of-flight. Generally to verify the solid state, morphology, and porosity of the medication.

MED-18. Among the FDM pharmaceutical polymers approved for consumption are [26]:

- Cellulose acetate

- Cellulose phthalate acetate

- Copovidone (Kollidon VA64)

- Ethylcellulose (EC)

- Hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC)

- Hydroxypropylcellulose (HPC)

- Hypromellose (HPMC)

- Hypromellose acetate succinate (HPMCAS)

- Hypromellose phthalate

- Maltodextrin

- Polycaprolactone (PCL)

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG)

- Polyethylene oxide (PEO)

- Polylactic acid (PLA)

- Polymethylmethacrylates (Eudragit)

- Polyoxyethylene sorbitan fatty acid esters (Polysorbate 20, Tween 20)

- Polyoxylglycerides (Gelucire)

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)

- Polyvinyl alcohol-polyethylene glycol graft copolymer (Kollicoat IR)

- Vinyl caprolactam-polyvinyl acetate-polyethylene glycol graft copolymer (Soluplus)

- Povidone (Kollidon PVP)

MED-19. Among the challenges and future perspectives highlighted are [12]:

- Digitalization and Innovation of the Production Lifecycle:** The development of cloud manufacturing platforms facilitates access control and intellectual property protection, with production at decentralized sites. This requires high security in data management and advanced supply chain management through predictive analytics.

- Control of Variables in Production: It is crucial to understand and control variables from digital design to the final product, considering the variability introduced by different brands of printers that can affect quality and standardization.

- Design and Cleaning of Medical Printers: Printers must have easily cleanable parts, be constructed with pharmaceutical-grade materials, and be located in cleanrooms, using biocompatible materials and allowing validations of pharmaceutical processes.

- Regulations for 3D Printed Pharmaceutical Products: The lack of specific regulatory guidelines may require individual efficiency and risk assessments per product, which can delay their implementation in healthcare. The classification of 3D printing (production technique or compound) affects regulatory requirements.

- 3D FDM Printing Production Speed: The production rate of this technique is slow compared to traditional manufacturing methods, limiting its use for mass production. It is anticipated that 3D printing will not completely replace traditional manufacturing but will act as a complementary production technique, suitable for specific cases where customization is highly desirable.

Please refer to the original bibliographic references or consult the References database or Medical database for more details.

References

[1] S. H. Lim, S. M. Y. Chia, L. Kang, and K. Y.-L. Yap, “Three-Dimensional Printing of Carbamazepine Sustained-Release Scaffold,” J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 105, no. 7, pp. 2155–2163, Jul. 2016.

[2] A. Melocchi et al., “Industrial Development of a 3D-Printed Nutraceutical Delivery Platform in the Form of a Multicompartment HPC Capsule,” AAPS PharmSciTech, vol. 19, no. 8, pp. 3343–3354, 2018.

[3] M. Saviano, “Design and production of personalised medicines via innovative 3D printing technologies,” Universita Degli Studi di Salerno, 2021.

[4] M. S. Algahtani, J. Ahmad, A. A. Mohammed, and M. Z. Ahmad, “Extrusion-based 3D printing for development of complex capsular systems for advanced drug delivery,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 663, no. July, p. 124550, 2024.

[5] G. K. Eleftheriadis, N. Genina, J. Boetker, and J. Rantanen, “Modular design principle based on compartmental drug delivery systems,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 178, p. 113921, 2021.

[6] R. Durga Prasad Reddy and V. Sharma, “Additive manufacturing in drug delivery applications: A review,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 589, no. June, p. 119820, 2020.

[7] A. G. Crișan et al., “QbD guided development of immediate release FDM-3D printed tablets with customizable API doses,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 613, no. October 2021, 2022.

[8] G. Manini, S. Benali, J. M. Raquez, and J. Goole, “Proof of concept of a predictive model of drug release from long-acting implants obtained by fused-deposition modeling,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 618, no. December 2021, p. 121663, 2022.

[9] M. Cui et al., “Opportunities and challenges of three-dimensional printing technology in pharmaceutical formulation development,” Acta Pharm. Sin. B, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 2488–2504, 2021.

[10] T. Tagami, N. Hayashi, N. Sakai, and T. Ozeki, “3D printing of unique water-soluble polymer-based suppository shell for controlled drug release,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 568, no. July, p. 118494, 2019.

[11] C. J. Boyer et al., “Three-Dimensional Printing Antimicrobial and Radiopaque Constructs,” 3D Print. Addit. Manuf., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 29–36, 2018.

[12] S. Henry, V. Vanhoorne, and C. Vervaet, Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) of Pharmaceuticals. 2023.

[13] S. Beg et al., “3D printing for drug delivery and biomedical applications,” Drug Discov. Today, vol. 25, no. 9, pp. 1668–1681, 2020.

[14] T. C. Okwuosa, D. Stefaniak, B. Arafat, A. Isreb, K. W. Wan, and M. A. Alhnan, “A Lower Temperature FDM 3D Printing for the Manufacture of Patient-Specific Immediate Release Tablets,” Pharm. Res., vol. 33, no. 11, pp. 2704–2712, 2016.

[15] T. C. Okwuosa, B. C. Pereira, B. Arafat, M. Cieszynska, A. Isreb, and M. A. Alhnan, “Fabricating a Shell-Core Delayed Release Tablet Using Dual FDM 3D Printing for Patient-Centred Therapy,” Pharm. Res., vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 427–437, 2017.

[16] M. Sadia et al., “Adaptation of pharmaceutical excipients to FDM 3D printing for the fabrication of patient-tailored immediate release tablets,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 513, no. 1–2, pp. 659–668, 2016.

[17] A. Goyanes et al., “Fabrication of controlled-release budesonide tablets via desktop (FDM) 3D printing,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 496, no. 2, pp. 414–420, 2015.

[18] C. Karavasili, G. K. Eleftheriadis, C. Gioumouxouzis, E. G. Andriotis, and D. G. Fatouros, “Mucosal drug delivery and 3D printing technologies: A focus on special patient populations,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 176, p. 113858, 2021.

[19] Y. Yang, H. Wang, H. Li, Z. Ou, and G. Yang, “3D printed tablets with internal scaffold structure using ethyl cellulose to achieve sustained ibuprofen release,” Eur. J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 115, no. January, pp. 11–18, 2018.

[20] S. J. Trenfield et al., “Track-and-trace: Novel anti-counterfeit measures for 3D printed personalized drug products using smart material inks,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 567, no. May, 2019.

[21] J. Y. Won et al., “3D printing of drug-loaded multi-shell rods for local delivery of bevacizumab and dexamethasone: A synergetic therapy for retinal vascular diseases,” Acta Biomater., vol. 116, pp. 174–185, 2020.

[22] J. Wang et al., “Emerging 3D printing technologies for drug delivery devices: Current status and future perspective,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 174, pp. 294–316, 2021.

[23] Z. Zhou et al., “Antimicrobial activity of 3D-printed poly(ε-Caprolactone) (PCL) composite scaffolds presenting vancomycin-loaded polylactic acid-glycolic acid (PLGA) microspheres,” Med. Sci. Monit., vol. 24, pp. 6934–6945, 2018.

[24] D. K. Mills, U. Jammalamadaka, K. Tappa, and J. Weisman, “Studies on the cytocompatibility, mechanical and antimicrobial properties of 3D printed poly(methyl methacrylate) beads,” Bioact. Mater., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 157–166, 2018.

[25] Z. Muwaffak, A. Goyanes, V. Clark, A. W. Basit, S. T. Hilton, and S. Gaisford, “Patient-specific 3D scanned and 3D printed antimicrobial polycaprolactone wound dressings,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 527, no. 1–2, pp. 161–170, 2017.

[26] R. Govender, E. O. Kissi, A. Larsson, and I. Tho, “Polymers in pharmaceutical additive manufacturing: A balancing act between printability and product performance,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 177, no. 0316, p. 113923, 2021.

[27] A. A. Mohammed, M. S. Algahtani, M. Z. Ahmad, J. Ahmad, and S. Kotta, “3D Printing in medicine: Technology overview and drug delivery applications,” Ann. 3D Print. Med., vol. 4, p. 100037, 2021.

[28] N. Paccione, V. Guarnizo-Herrero, M. Ramalingam, E. Larrarte, and J. L. Pedraz, “Application of 3D printing on the design and development of pharmaceutical oral dosage forms,” J. Control. Release, vol. 373, no. March, pp. 463–480, 2024.

[29] H. Hatami, M. M. Mojahedian, P. Kesharwani, and A. Sahebkar, “Advancing personalized medicine with 3D printed combination drug therapies: A comprehensive review of application in various conditions,” Eur. Polym. J., vol. 215, no. May, p. 113245, 2024.

[30] A. Mohammed, A. Elshaer, P. Sareh, M. Elsayed, and H. Hassanin, “Additive Manufacturing Technologies for Drug Delivery Applications,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 580, no. January, p. 119245, 2020.

[31] H. Ragelle et al., “Additive manufacturing in drug delivery: Innovative drug product design and opportunities for industrial application,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 178, 2021.

[32] C. L. Caudill, J. L. Perry, S. Tian, J. C. Luft, and J. M. DeSimone, “Spatially controlled coating of continuous liquid Interface production microneedles for transdermal protein delivery,” J. Control. Release, vol. 284, no. February, pp. 122–132, 2018.

[33] M. A. Luzuriaga, D. R. Berry, J. C. Reagan, R. A. Smaldone, and J. J. Gassensmith, “Biodegradable 3D printed polymer microneedles for transdermal drug delivery,” Lab Chip, vol. 18, no. 8, pp. 1223–1230, 2018.

[34] K. Pietrzak, A. Isreb, and M. A. Alhnan, “A flexible-dose dispenser for immediate and extended release 3D printed tablets,” Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm., vol. 96, pp. 380–387, 2015.

[35] B. C. Pereira et al., “‘Temporary Plasticiser’: A novel solution to fabricate 3D printed patient-centred cardiovascular ‘Polypill’ architectures,” Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm., vol. 135, no. December 2018, pp. 94–103, 2019.

[36] A. Alzahrani et al., “Fabrication of a shell-core fixed-dose combination tablet using fused deposition modeling 3D printing,” Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm., vol. 177, no. July, pp. 211–223, 2022.

[37] B. C. Pereira, A. Isreb, M. Isreb, R. T. Forbes, E. F. Oga, and M. A. Alhnan, “Additive Manufacturing of a Point-of-Care ‘Polypill:’ Fabrication of Concept Capsules of Complex Geometry with Bespoke Release against Cardiovascular Disease,” Adv. Healthc. Mater., vol. 9, no. 13, pp. 1–12, 2020.

[38] H. Windolf, R. Chamberlain, and J. Breitkreutz, “3D Printed Mini-Floating-Polypill for Parkinson ’ s Disease : Combination of Levodopa , Benserazide , and Pramipexole in Various Dosing for Personalized Therapy,” 2022.

[39] J. Krause, L. Müller, D. Sarwinska, A. Seidlitz, M. Sznitowska, and W. Weitschies, “3D printing of mini tablets for pediatric use,” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 1–16, 2021.

[40] N. Scoutaris, S. A. Ross, and D. Douroumis, “3D Printed ‘Starmix’ Drug Loaded Dosage Forms for Paediatric Applications,” Pharm. Res., vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 1–11, 2018.

[41] K. Huanbutta, P. Sriamornsak, T. Kittanaphon, K. Suwanpitak, N. Klinkesorn, and T. Sangnim, “Development of a zero-order kinetics drug release floating tablet with anti–flip-up design fabricated by 3D-printing technique,” J. Pharm. Investig., vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 213–222, 2021.

[42] C. I. Gioumouxouzis et al., “A 3D printed bilayer oral solid dosage form combining metformin for prolonged and glimepiride for immediate drug delivery,” Eur. J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 120, no. April, pp. 40–52, 2018.

[43] M. Ibrahim et al., “3D Printing of Metformin HCl PVA Tablets by Fused Deposition Modeling: Drug Loading, Tablet Design, and Dissolution Studies,” AAPS PharmSciTech, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 1–11, 2019.

[44] G. Verstraete et al., “3D printing of high drug loaded dosage forms using thermoplastic polyurethanes,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 536, no. 1, pp. 318–325, 2018.

[45] B. J. Anaya et al., “Engineering of 3D printed personalized polypills for the treatment of the metabolic syndrome,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 642, no. April, 2023.

[46] M. Chen et al., “Co-delivery of siRNA and doxorubicin to cancer cells from additively manufactured implants,” RSC Adv., vol. 5, no. 123, pp. 101718–101725, 2015.

[47] M. Chen et al., “Fabrication and characterization of a rapid prototyped tissue engineering scaffold with embedded multicomponent matrix for controlled drug release,” Int. J. Nanomedicine, vol. 7, pp. 4285–4297, 2012.

[48] X. Zhang et al., “3D printed PCLA scaffold with nano-hydroxyapatite coating doped green tea EGCG promotes bone growth and inhibits multidrug-resistant bacteria colonization,” Cell Prolif., vol. 55, no. 10, pp. 1–15, 2022.

[49] I. Tse et al., “Antimicrobial activity of 3d-printed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (Abs) polymer-coated with silver nanoparticles,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 14, no. 24, 2021.

[50] A. Ghanizadeh Tabriz et al., “3D printed bilayer tablet with dual controlled drug release for tuberculosis treatment,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 593, no. December 2020, p. 120147, 2021.

[51] N. Genina, J. P. Boetker, S. Colombo, N. Harmankaya, J. Rantanen, and A. Bohr, “Anti-tuberculosis drug combination for controlled oral delivery using 3D printed compartmental dosage forms: From drug product design to in vivo testing,” J. Control. Release, vol. 268, no. August, pp. 40–48, 2017.

[52] A. Awad, A. Yao, S. J. Trenfield, A. Goyanes, S. Gaisford, and A. W. Basit, “3D printed tablets (Printlets) with braille and moon patterns for visually impaired patients,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 1–14, 2020.

[53] S. Trenfield, A. Basit, and A. Goyanes, “INNOVATIONS IN 3D: Printed pharmaceuticals,” ONdrugDelivery, vol. 2020, no. 109, pp. 45–49, 2020.

[54] A. Goyanes et al., “Automated therapy preparation of isoleucine formulations using 3D printing for the treatment of MSUD: First single-centre, prospective, crossover study in patients,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 567, no. July, p. 118497, 2019.

[55] J. J. Ong et al., “3D printed opioid medicines with alcohol-resistant and abuse-deterrent properties,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 579, no. January, p. 119169, 2020.

[56] I. Salahshoori et al., “Simulation-based approaches for drug delivery systems: Navigating advancements, opportunities, and challenges,” J. Mol. Liq., vol. 395, no. December 2023, p. 123888, 2024.

[57] M. Elbadawi et al., “M3DISEEN: A novel machine learning approach for predicting the 3D printability of medicines,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 590, no. August, p. 119837, 2020.

[58] M. Elbadawi et al., “Disrupting 3D printing of medicines with machine learning,” Trends Pharmacol. Sci., vol. 42, no. 9, pp. 745–757, 2021.

[59] A. Dedeloudi, E. Weaver, and D. A. Lamprou, “Machine learning in additive manufacturing & Microfluidics for smarter and safer drug delivery systems,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 636, no. January, p. 122818, 2023.

[60] B. Muñiz Castro et al., “Machine learning predicts 3D printing performance of over 900 drug delivery systems,” J. Control. Release, vol. 337, no. July, pp. 530–545, 2021.

[61] M. Elbadawi, T. Gustaffson, S. Gaisford, and A. W. Basit, “3D printing tablets: Predicting printability and drug dissolution from rheological data,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 590, no. July, p. 119868, 2020.

[62] Y. M. Than and V. Titapiwatanakun, “Tailoring immediate release FDM 3D printed tablets using a quality by design (QbD) approach,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 599, no. January, p. 120402, 2021.

[63] S. Obeid, M. Madžarević, M. Krkobabić, and S. Ibrić, “Predicting drug release from diazepam FDM printed tablets using deep learning approach: Influence of process parameters and tablet surface/volume ratio,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 601, no. March, 2021.

[64] J. R. Cerda et al., “Personalised 3d printed medicines: Optimising material properties for successful passive diffusion loading of filaments for fused deposition modelling of solid dosage forms,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 12, no. 4, 2020.