FFF vs FDM

This page explains the differences between FFF and FDM and presents an example table with features of commercial 3D printers.

Among the AM processes, material extrusion (MEX) is one of the most widely used, which includes Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) or Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) [1], [2]. In addition, FDM has been one of the most studied AM processes in the past decade (2010-2020), with a frequency of 20.09% [3].

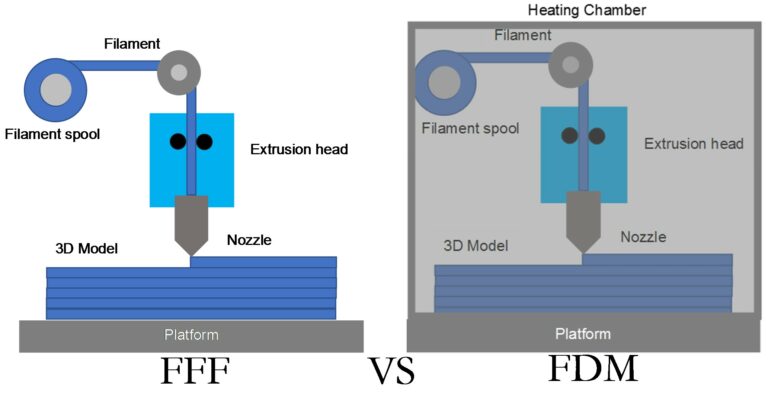

For another hand, FDM and FFF refer to the same process. While Stratasys first used FDM commercially, FFF was first coined by the hobbyist community for the same AM process.

In addition, a desktop-grade 3D printer stands out for its inexpensive [4] and open technology, which makes it accessible to any microenterprise or individual. The economy translates into a competitive advantage in terms of the product cost, especially in small batch production or individualized products; whose manufacture is prohibited at low production rates for other conventional processes, for example, injection molding (IM) [5].

On the other hand, an industrial-grade 3D printer, equipped with a heating chamber (see Figure) and extruder, reaches higher temperatures, and enables the processing of robust materials like polyether ether ketone (PEEK) or polyetherimide (PEI or ULTEM®). These materials find applications in the medical and aerospace industries. However, industrial-grade printers are more expensive due to their specialized equipment and materials, making them more accessible to medium and large companies [4], [6], [7].

In this web page, “FFF” refers to desktop-grade printers and “FDM” to industrial-grade printers.

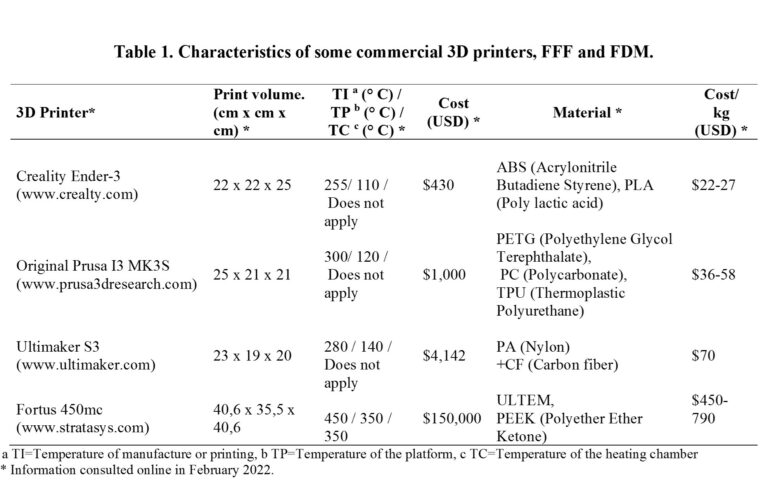

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of various 3D printers and materials, all of which are FFF, except for the Fortus 450 mc, a Stratasys FDM.

In Table 1, notable differences include the cost factor, with FDM printers being 29 to 349 times more expensive than FFF printers. FFF printers generally operate at temperatures below 300°C and lack heating chambers. Raw material costs remain consistent between the two technologies. However, FDM printers, due to their higher temperatures, can handle a wider range of materials, including high-performance options like PEEK (polyether-ether-ketone), commonly used in medical implants.

The materials produced by both technologies exhibit disparities in impact strength [8] and tensile, flexural strength, and elastic modulus of ABS samples [9]. Overall, the mechanical strength-to-cost ratio favors FFF printers, making them a more cost-effective choice. This cost advantage positions FFF products attractively in the market.

References

[1] L. L. Lopez Taborda, H. Maury, and J. Pacheco, “Design for additive manufacturing: a comprehensive review of the tendencies and limitations of methodologies,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 918–966, Jun. 2021.

[2] D. C. F, K. Stefan, and W. S. M, “The impact of additive manufacturing on supply chains,” Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag., vol. 47, no. 10, pp. 954–971, 2017.

[3] R. Jemghili, A. Ait Taleb, and M. Khalifa, “A bibliometric indicators analysis of additive manufacturing research trends from 2010 to 2020,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 1432–1454, 2021.

[4] M. Yosofi, O. Kerbrat, and P. Mognol, “Framework to Combine Technical, Economic and Environmental Points of View of Additive Manufacturing Processes,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 69, pp. 118–123, 2018.

[5] E. Atzeni, L. Iuliano, P. Minetola, and A. Salmi, “Redesign and cost estimation of rapid manufactured plastic parts,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 308–317, 2010.

[6] M. A. H. Khondoker, A. Asad, and D. Sameoto, “Printing with mechanically interlocked extrudates using a custom bi-extruder for fused deposition modelling,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 921–934, 2018.

[7] C. H. P. Mello, R. C. Martins, B. R. Parra, E. de Oliveira Pamplona, E. G. Salgado, and R. T. Seguso, “Systematic proposal to calculate price of prototypes manufactured through rapid prototyping an FDM 3D printer in a university lab,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 411–416, Oct. 2010.

[8] D. A. Roberson, A. R. T. Perez, C. M. Shemelya, A. Rivera, E. MacDonald, and R. B. Wicker, “Comparison of stress concentrator fabrication for 3D printed polymeric izod impact test specimens,” Addit. Manuf., vol. 7, pp. 1–3, 2015.

[9] M. Seidl, J. Safka, J. Bobek, L. Behalek, and J. Habr, “{MECHANICAL} {PROPERTIES} {OF} {PRODUCTS} {MADE} {OF} {ABS} {WITH} {RESPECT} {TO} {INDIVIDUALITY} {OF} {FDM} {PRODUCTION} {PROCESSES},” {MM} Sci. J., vol. 2017, no. 01, pp. 1748–1751, Feb. 2017.