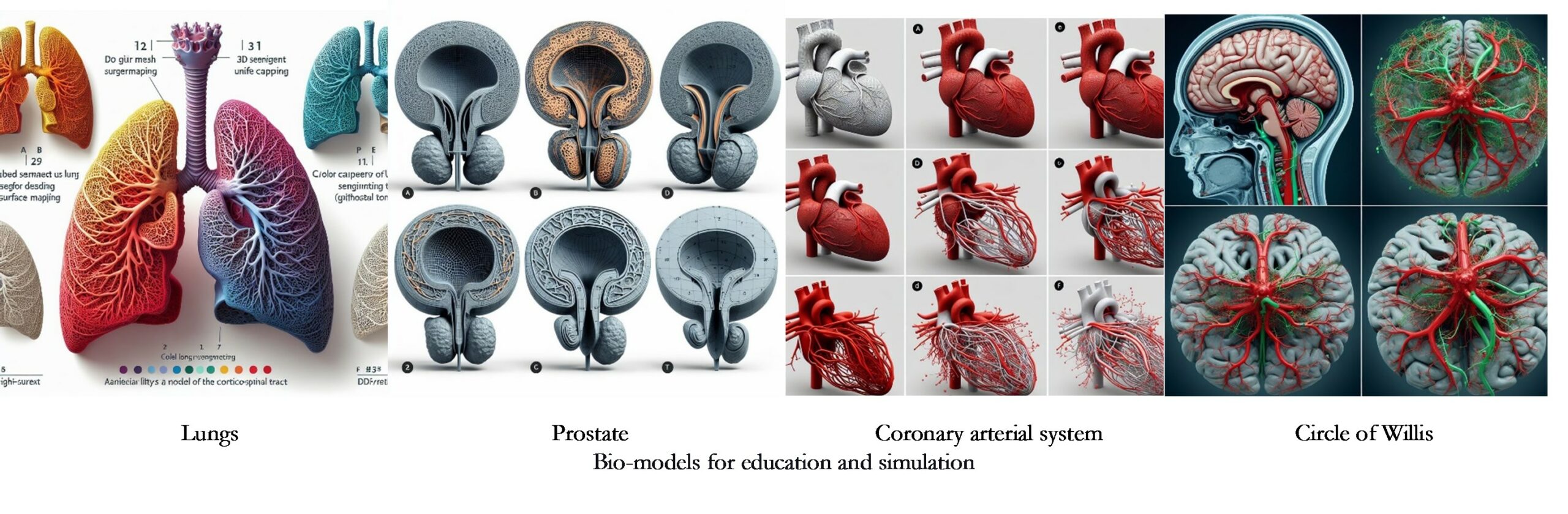

Bio-models for education and simulation (BM-E&S)

Next, there are some guidelines for medical and individualized cases with their coding, obtained after analyzing the respective references, and grouped by case study and common trends, highlighting in bold the competitive advantages that can become innovations.

BM-E&S-01. Materials should be selected based on the desired properties of the simulated tissue or organ, particularly hardness and modulus. For example:

- Soft tissues like the brain can be simulated using silicones or low-hardness materials such as Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU), with synthetic silicone offering reusability.

- Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) may be suitable for hard tissues like bones.

- Polyamide (PA) can be considered for tissues or organs with intermediate hardness and stiffness, such as the lungs [1]–[4].

.

BM-E&S-02. Suppose the process does not handle the material with the required hardness or color. In that case, the FFF process can be used indirectly by printing the model to make the mold or directly printing the mold so that the use of FFF is not restricted only to available materials but is extended by the possibilities of other processes such as casting and molding [1]–[4].

BM-E&S-03. The esthetics should be like that of the original tissue or organ. If the process does not handle the specific color, it can be painted or incorporated during the process. The surface can be polished or diluted if the texture is different. The most suitable material in this case is ABS [1], [2].

BM-E&S-04. Once the simulator has been designed and manufactured, it should be tested by suitable professionals to measure the degree to which it can be useful, reproducible, and like the real experience [3], [4].

BM-E&S-05. The hardness and modulus of rigidity of the tissues or organs to be simulated should be measured to compare with the material properties and manufacturing process and decide on the direct or indirect use of FFF To specify the simulator’s lifetime, include tests or information on the deterioration of simulator properties over time. However, this does not detract from the value of testing by suitable professionals, despite the differences between original organ properties and simulator material [3], [4].

BM-E&S-06. Digital models can be extracted from CT or MRI scans of patients or taken from digital libraries free of charge and modified to ensure low cost by downscaling but without weakening the walls of the material; ensure a modular design, which facilitates maintenance of the simulator or replacement of parts due to wear or use; ensure a modular design that facilitates assembly during fabrication; or incorporate features that the digital model does not include due to CT or MRI resolution, such as vessels, or otherwise remove features not feasible to fabricate due to the resolution of the 3D printer [1], [2], [3], [4].

BM-E&S-07. Materials cost 50 to 1000 USD, only sometimes including labor, design, and equipment costs. Fabrication time can be up to 24 hours, and a refill per use is 10 USD. These prices and times depend on the specific organ and procedure to be simulated [3], [4].

Please refer to the original bibliographic references or consult the References database or Medical database for more details.

References

[1] O. C. Burdall, E. Makin, M. Davenport, and N. Ade-Ajayi, “3D printing to simulate laparoscopic choledochal surgery,” J. Pediatr. Surg., vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 828–831, May 2016.

[2] J. R. Ryan, K. K. Almefty, P. Nakaji, and D. H. Frakes, “Cerebral Aneurysm Clipping Surgery Simulation Using Patient-Specific 3D Printing and Silicone Casting,” World Neurosurg., vol. 88, pp. 175–181, 2016.

[3] R. Javan, D. Herrin, and A. Tangestanipoor, “Understanding Spatially Complex Segmental and Branch Anatomy Using 3D Printing,” Acad. Radiol., vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 1183–1189, Sep. 2016.

[4] C. C. Ploch, C. S. S. A. Mansi, J. Jayamohan, and E. Kuhl, “Using 3D Printing to Create Personalized Brain Models for Neurosurgical Training and Preoperative Planning,” World Neurosurg., vol. 90, pp. 668–674, Jun. 2016.