Database for Medical and personalization applications.

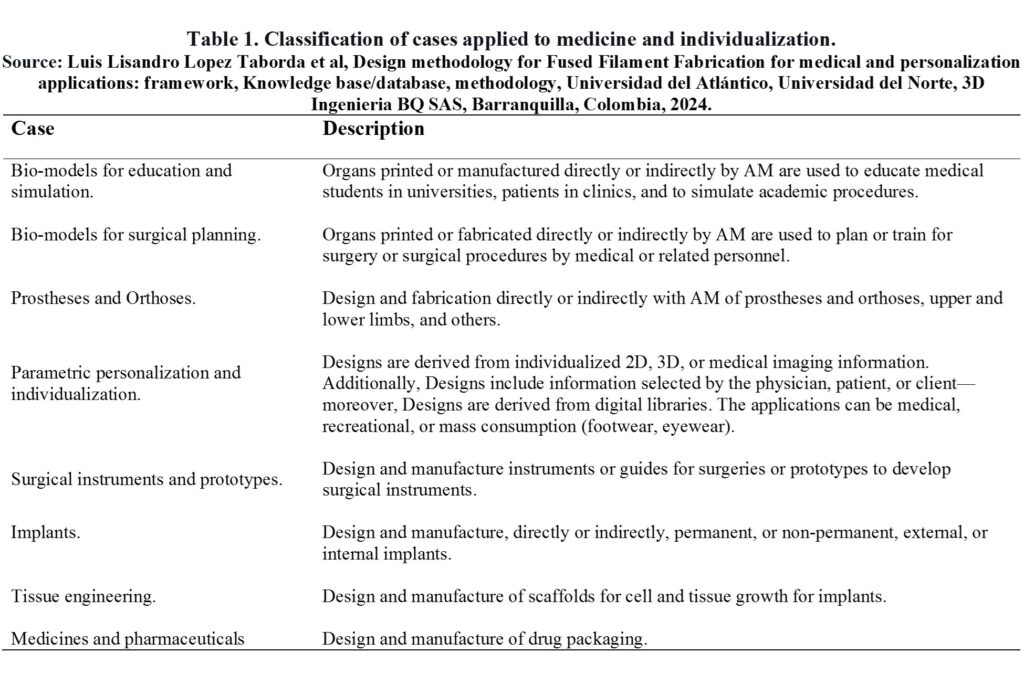

Table 1 summarizes the classification and description of the cases applied to medicine and individualization found during the documentary review’s analysis.

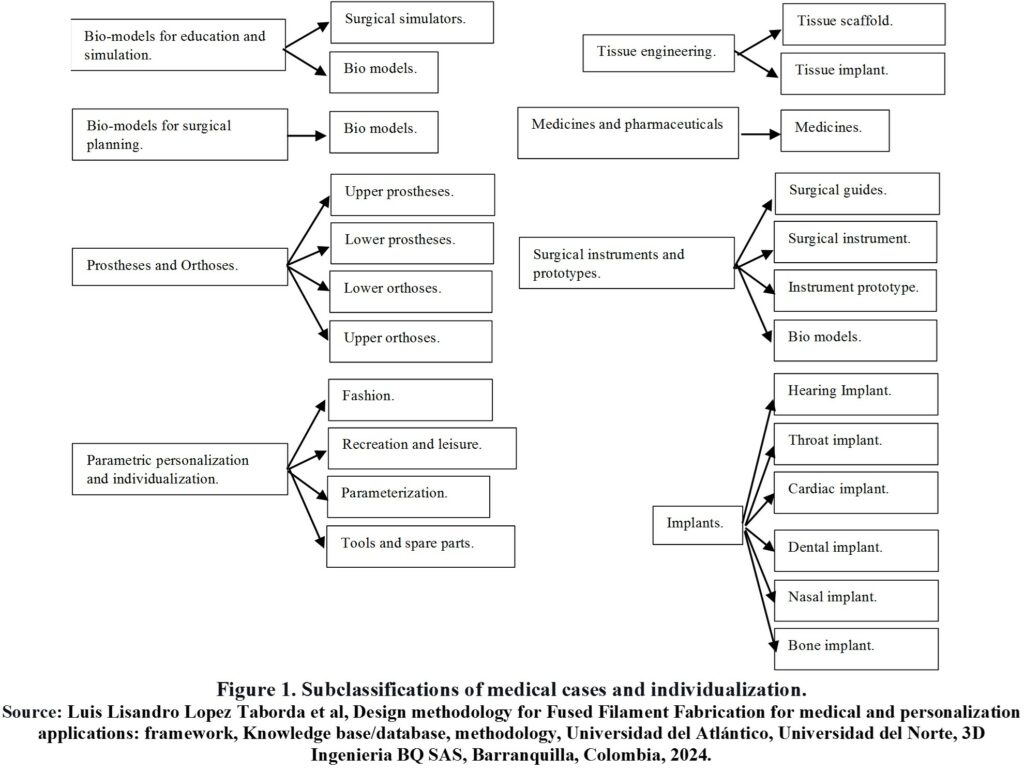

Figure 1 summarizes the medical case subclassifications and individualization that were obtained.

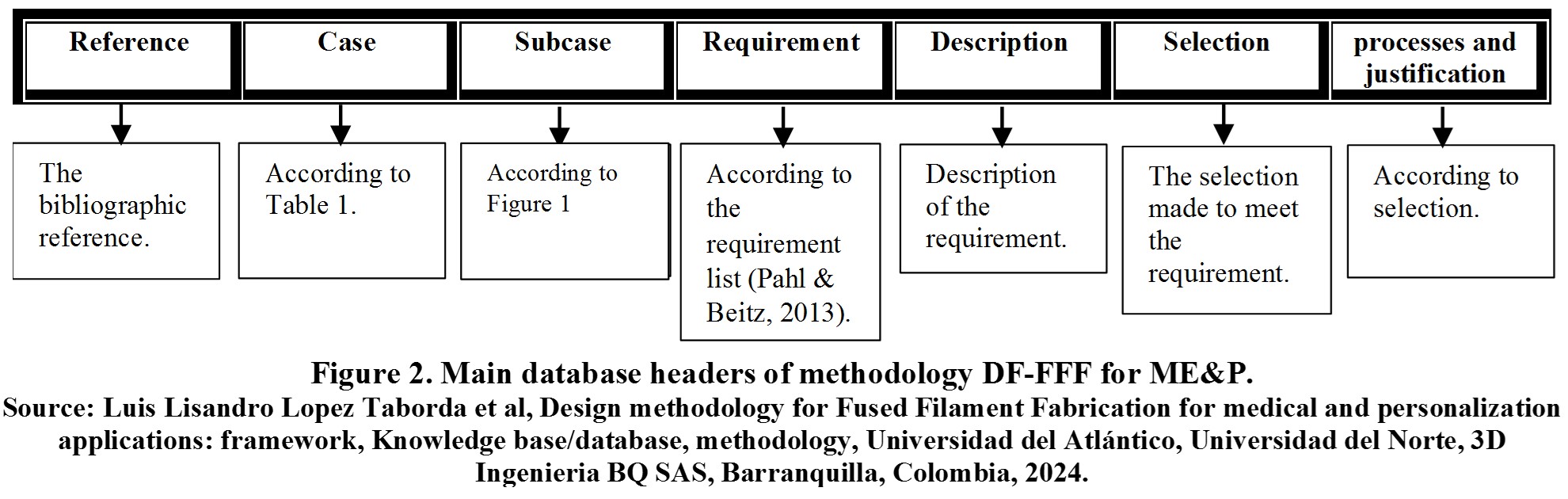

Figure 2 summarizes the main headings of the database.

Below is a detailed explanation of each heading in Figure 2.

- Reference: Contains the bibliographic reference analyzed to generate specific and general guidelines.

- Case:One (1) of the eight (8) cases in Table 1 in which the analyzed reference can be classified.

- Subcase:Some of the specific products or sub-cases in Figure 1, depending on the case to which the reference belongs.

- Requirement: It is a demand, obligation, or desirable quality to be met by the product. The product has more than one, and it is defined from the analysis of the reference and requirement lists in the specialized bibliography [1], [2], among others.

- Description: Description of each requirement of a specific product or analyzed case.

- Selection:It is a decision or selection of a product specification to meet a requirement.

- Process and justification: Process using which the product specification is defined.

Under each heading or column is the respective information, and each row contains information related to a specific case or reference. The purpose is to search according to the desired case to apply the guidelines of other cases to one’s case. In case of detailed information, the reference can be consulted directly.

Consult the database of medical cases and personalization below [3]-[4].

Medical & Personalization

| Group | case | subcase | References | objective | Method | Results | Conclusions | requirement | Description | Selection | Process/ Justification/ Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME6 | Design, Manufacture with 3D printing, and test a Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator for the Common Bile Duct. | Digital images of hepatic anatomy and standard dimensions of a laparoscopic trainer were used to create a beginner-level laparoscopic choledochal surgery model. The design was manufactured using a Systems 660pro machine (SLS) with VisiJet PXL powder to create a liver mold. This included a cuboid portal in which disposable hybrid components representing the hepatic and pancreatic ducts and the choledochal cyst were fitted. The mold was used to create soft silicone replicas with T28 resin and T5 fast catalyst. The model was evaluated on a national pediatric surgery training day. | The 10 delegates who tested the simulation felt that the tactile similarity was good (5.6/10 ± 1.71, 10 = like the real thing), it was not too complex (6.2/10 ± 1.35; where 1 = too simple, 10 = too complicated), and overall very useful (7.36/10 ± 1.57, 10 = invaluable). 100% stated that they felt they could reproduce this in their own centers, and 100% would recommend this simulation to their colleagues. | Although this first phase of simulation of excision of choledochal cysts requires further development, 3D printing provides a useful means to create specific and detailed simulations for rare and complex operations with great potential for development. | Simulator material | The simulator material must resemble the real tissues that will be intervened | Soft silicone with T28 resin and fast T5 catalyst (1:20 catalyst:silicone). | Soft material that simulates soft tissues |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME6 | Design, Manufacture with 3D printing, and test a Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator for the Common Bile Duct. | Digital images of hepatic anatomy and standard dimensions of a laparoscopic trainer were used to create a beginner-level laparoscopic choledochal surgery model. The design was manufactured using a Systems 660pro machine (SLS) with VisiJet PXL powder to create a liver mold. This included a cuboid portal in which disposable hybrid components representing the hepatic and pancreatic ducts and the choledochal cyst were fitted. The mold was used to create soft silicone replicas with T28 resin and T5 fast catalyst. The model was evaluated on a national pediatric surgery training day. | The 10 delegates who tested the simulation felt that the tactile similarity was good (5.6/10 ± 1.71, 10 = like the real thing), it was not too complex (6.2/10 ± 1.35; where 1 = too simple, 10 = too complicated), and overall very useful (7.36/10 ± 1.57, 10 = invaluable). 100% stated that they felt they could reproduce this in their own centers, and 100% would recommend this simulation to their colleagues. | Although this first phase of simulation of excision of choledochal cysts requires further development, 3D printing provides a useful means to create specific and detailed simulations for rare and complex operations with great potential for development. | Simulator insert material | The cuboid portal was to be filled with a disposable and reusable simulated bile tree: The simulator material must resemble the hardness of the real tissues to be operated on. | This included a square sponge with an embedded balloon inside, a surgical glove finger to simulate dilated proximity ducts, and an electrical cable insulation tube to represent the bile and common pancreatic ducts (conventional materials). | Ability to reuse the simulator, reduce the cost of the simulator, Soft material that simulates soft tissues |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME6 | Design, Manufacture with 3D printing, and test a Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator for the Common Bile Duct. | Digital images of hepatic anatomy and standard dimensions of a laparoscopic trainer were used to create a beginner-level laparoscopic choledochal surgery model. The design was manufactured using a Systems 660pro machine (SLS) with VisiJet PXL powder to create a liver mold. This included a cuboid portal in which disposable hybrid components representing the hepatic and pancreatic ducts and the choledochal cyst were fitted. The mold was used to create soft silicone replicas with T28 resin and T5 fast catalyst. The model was evaluated on a national pediatric surgery training day. | The 10 delegates who tested the simulation felt that the tactile similarity was good (5.6/10 ± 1.71, 10 = like the real thing), it was not too complex (6.2/10 ± 1.35; where 1 = too simple, 10 = too complicated), and overall very useful (7.36/10 ± 1.57, 10 = invaluable). 100% stated that they felt they could reproduce this in their own centers, and 100% would recommend this simulation to their colleagues. | Although this first phase of simulation of excision of choledochal cysts requires further development, 3D printing provides a useful means to create specific and detailed simulations for rare and complex operations with great potential for development. | Insert simulator geometry | The cuboid portal should be filled with a disposable and reusable simulated bile tree: The geometry should be as similar as possible to that of a real and average patient. | This included a square sponge with an embedded balloon inside, a surgical glove finger to simulate dilated proximity ducts, and an electrical cable insulation tube to represent the bile and common pancreatic ducts (conventional materials). | Ability to reuse the simulator, reduce the simulator |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME6 | Design, Manufacture with 3D printing, and test a Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator for the Common Bile Duct. | Digital images of hepatic anatomy and standard dimensions of a laparoscopic trainer were used to create a beginner-level laparoscopic choledochal surgery model. The design was manufactured using a Systems 660pro machine (SLS) with VisiJet PXL powder to create a liver mold. This included a cuboid portal in which disposable hybrid components representing the hepatic and pancreatic ducts and the choledochal cyst were fitted. The mold was used to create soft silicone replicas with T28 resin and T5 fast catalyst. The model was evaluated on a national pediatric surgery training day. | The 10 delegates who tested the simulation felt that the tactile similarity was good (5.6/10 ± 1.71, 10 = like the real thing), it was not too complex (6.2/10 ± 1.35; where 1 = too simple, 10 = too complicated), and overall very useful (7.36/10 ± 1.57, 10 = invaluable). 100% stated that they felt they could reproduce this in their own centers, and 100% would recommend this simulation to their colleagues. | Although this first phase of simulation of excision of choledochal cysts requires further development, 3D printing provides a useful means to create specific and detailed simulations for rare and complex operations with great potential for development. | Simulator Geometry | The geometry should be as close as possible to that of a real and average patient. | The translated value of the provided data Se emplearon imágenes hepáticas y dimensiones de simuladores estándar in English is Liver images and standard simulator dimensions were used. | Simulate the real experience |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME6 | Design, Manufacture with 3D printing, and test a Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator for the Common Bile Duct. | Digital images of hepatic anatomy and standard dimensions of a laparoscopic trainer were used to create a beginner-level laparoscopic choledochal surgery model. The design was manufactured using a Systems 660pro machine (SLS) with VisiJet PXL powder to create a liver mold. This included a cuboid portal in which disposable hybrid components representing the hepatic and pancreatic ducts and the choledochal cyst were fitted. The mold was used to create soft silicone replicas with T28 resin and T5 fast catalyst. The model was evaluated on a national pediatric surgery training day. | The 10 delegates who tested the simulation felt that the tactile similarity was good (5.6/10 ± 1.71, 10 = like the real thing), it was not too complex (6.2/10 ± 1.35; where 1 = too simple, 10 = too complicated), and overall very useful (7.36/10 ± 1.57, 10 = invaluable). 100% stated that they felt they could reproduce this in their own centers, and 100% would recommend this simulation to their colleagues. | Although this first phase of simulation of excision of choledochal cysts requires further development, 3D printing provides a useful means to create specific and detailed simulations for rare and complex operations with great potential for development. | Geometry of the Mold | The geometry should be as close as possible to that of a real and average patient. | Rectangular mold with external dimensions of standard simulator. | Simulate the real experience |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME6 | Design, Manufacture with 3D printing, and test a Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator for the Common Bile Duct. | Digital images of hepatic anatomy and standard dimensions of a laparoscopic trainer were used to create a beginner-level laparoscopic choledochal surgery model. The design was manufactured using a Systems 660pro machine (SLS) with VisiJet PXL powder to create a liver mold. This included a cuboid portal in which disposable hybrid components representing the hepatic and pancreatic ducts and the choledochal cyst were fitted. The mold was used to create soft silicone replicas with T28 resin and T5 fast catalyst. The model was evaluated on a national pediatric surgery training day. | The 10 delegates who tested the simulation felt that the tactile similarity was good (5.6/10 ± 1.71, 10 = like the real thing), it was not too complex (6.2/10 ± 1.35; where 1 = too simple, 10 = too complicated), and overall very useful (7.36/10 ± 1.57, 10 = invaluable). 100% stated that they felt they could reproduce this in their own centers, and 100% would recommend this simulation to their colleagues. | Although this first phase of simulation of excision of choledochal cysts requires further development, 3D printing provides a useful means to create specific and detailed simulations for rare and complex operations with great potential for development. | Mold Material | The material must guarantee the geometry of the simulator and facilitate demolding. | Nylon powder (visijet pxl), for demolding silicone spray is used Ambersil Formula 5 (manufactured in available laser sintering selective printer, 3D systems project 660pro) | Manufacturing facility |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME6 | Design, Manufacture with 3D printing, and test a Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator for the Common Bile Duct. | Digital images of hepatic anatomy and standard dimensions of a laparoscopic trainer were used to create a beginner-level laparoscopic choledochal surgery model. The design was manufactured using a Systems 660pro machine (SLS) with VisiJet PXL powder to create a liver mold. This included a cuboid portal in which disposable hybrid components representing the hepatic and pancreatic ducts and the choledochal cyst were fitted. The mold was used to create soft silicone replicas with T28 resin and T5 fast catalyst. The model was evaluated on a national pediatric surgery training day. | The 10 delegates who tested the simulation felt that the tactile similarity was good (5.6/10 ± 1.71, 10 = like the real thing), it was not too complex (6.2/10 ± 1.35; where 1 = too simple, 10 = too complicated), and overall very useful (7.36/10 ± 1.57, 10 = invaluable). 100% stated that they felt they could reproduce this in their own centers, and 100% would recommend this simulation to their colleagues. | Although this first phase of simulation of excision of choledochal cysts requires further development, 3D printing provides a useful means to create specific and detailed simulations for rare and complex operations with great potential for development. | Simulator Configuration | It should be complex enough to be useful in training but simple enough to ensure the education and reproducibility of the procedure with the same simulator, and in other centers. | Simulator consisting of two parts, the larger one representing the patient's exterior, and an insert containing a biliary tree that would represent the tissue to be accessed with laparoscopy. | guarantee utility, reduce costs, and increase reproducibility and reusability. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME6 | Design, Manufacture with 3D printing, and test a Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator for the Common Bile Duct. | Digital images of hepatic anatomy and standard dimensions of a laparoscopic trainer were used to create a beginner-level laparoscopic choledochal surgery model. The design was manufactured using a Systems 660pro machine (SLS) with VisiJet PXL powder to create a liver mold. This included a cuboid portal in which disposable hybrid components representing the hepatic and pancreatic ducts and the choledochal cyst were fitted. The mold was used to create soft silicone replicas with T28 resin and T5 fast catalyst. The model was evaluated on a national pediatric surgery training day. | The 10 delegates who tested the simulation felt that the tactile similarity was good (5.6/10 ± 1.71, 10 = like the real thing), it was not too complex (6.2/10 ± 1.35; where 1 = too simple, 10 = too complicated), and overall very useful (7.36/10 ± 1.57, 10 = invaluable). 100% stated that they felt they could reproduce this in their own centers, and 100% would recommend this simulation to their colleagues. | Although this first phase of simulation of excision of choledochal cysts requires further development, 3D printing provides a useful means to create specific and detailed simulations for rare and complex operations with great potential for development. | Functionality test | Professionals related must test the simulator and provide feedback with their opinion. | Twenty senior pediatric surgical apprentices attended the national competition. training day. The biliary station consisted of two parts: simulated laparoscopic cholecystectomy with porcine organs and simulated choledochal cyst as described. Ten delegates tested the latest simulation. Feedback was collected from the 10. | In visual analog scoring, the simulation obtained an average of 5.6 / 10 (range: 3-8; SD 1.71), where 10 means it feels like the real operation and 1 was not at all the same. Delegates felt that the complexity was scored correctly with an average of 6.2 / 10 (range: 4-8; SD 1.35), where 1 = too simple and 10 = too complicated. The simulation was also considered very useful overall with an average of 7.36 / 10 (range: 4-9; SD 1.57), where 1 = useless and 10 = invaluable. It was considered easily reproducible in their own units and 100% also claimed they would recommend the simulation to their colleagues. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME12 | Design and Manufacture with 3D printing, Anatomical models for teaching | They graphically designed 3D meshes or modified imported data from cross-sectional images to develop physical models specifically for teaching complex segments and branches of anatomy. 3D printing itself is easily accessible through online commercial services, and the models are made of polyamide or plaster. | Anatomical models of the liver, lungs, prostate, coronary arteries, and the Circle of Willis were created. These models have advantages that include customizable details, relative low cost, complete control of design focused on subsegments, potential for color coding, and the use of cross-sectional images combined with graphic design. | The radiologists have the opportunity to serve as leaders in medical education and clinical care with 3D printed models that provide beneficial interaction with patients, physicians, and learners in all specialties, proactively assuming the role of educator. Complex models can be developed to demonstrate normal anatomy or common pathology for medical education purposes. There is a need for randomized trials, which radiologists can design, to demonstrate the utility and effectiveness of 3D printed models for teaching simple and complex anatomy, simulating interventions, measuring patient satisfaction, and improving clinical care. | Simulator material | The translated value of El material debe ser durable in English is The material must be durable. | Nylon (manufacturing by remote 3D printing) | Durability of the Material |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME12 | Design and Manufacture with 3D printing, Anatomical models for teaching | They graphically designed 3D meshes or modified imported data from cross-sectional images to develop physical models specifically for teaching complex segments and branches of anatomy. 3D printing itself is easily accessible through online commercial services, and the models are made of polyamide or plaster. | Anatomical models of the liver, lungs, prostate, coronary arteries, and the Circle of Willis were created. These models have advantages that include customizable details, relative low cost, complete control of design focused on subsegments, potential for color coding, and the use of cross-sectional images combined with graphic design. | The radiologists have the opportunity to serve as leaders in medical education and clinical care with 3D printed models that provide beneficial interaction with patients, physicians, and learners in all specialties, proactively assuming the role of educator. Complex models can be developed to demonstrate normal anatomy or common pathology for medical education purposes. There is a need for randomized trials, which radiologists can design, to demonstrate the utility and effectiveness of 3D printed models for teaching simple and complex anatomy, simulating interventions, measuring patient satisfaction, and improving clinical care. | Simulator Geometry | The geometry must correspond to the anatomy of the specific organ, including vessels, arteries, connections, even the use of colors, voids, and sections (assembly) to better illustrate the anatomical composition. | The pulmonary model: The initial digital 3D mesh is graphically designed and obtained from the online library free of charge (3DCADBrowser.com). Modifications were made using a free version of Autodesk 3D Studio Max with a student/educator license to add the main pulmonary arteries to provide the connection between each lung, as well as to create a surface color map representing the lobes and segments of the lungs. The hepatic model: 2D diagrams were hand-drawn to communicate liver cutting planes. A graphic designer was hired, whose services were available as a freelance artist for an online fee (FlatPyramid.com). Multiple instances of corrections had to be made to achieve the final ideal model. The coronary arterial system was part of a pre-designed cardiopulmonary system commercially available and through an online catalog of professional 3D models (TurboSquid.com). Minor modifications were required using graphic design software (Autodesk 3D Studio Max, San Rafael, CA, USA), including the addition of the septal branches of the left anterior descending artery, as well as increasing the diameter of all vessels. 3D prostate model: It was obtained from a free online source that had already been reconstructed in 3D from MRI using open-source Slicer software (Slicer.org). The posterior anatomical subdivision was performed in Autodesk 3D Studio Max, which requires intermediate-level graphic design skills and considerations on how the components of the final model can fit together in the physical world like puzzle pieces. The overall curvature of the urethra was reduced, and a gradual decrease was applied to the urethral prostate. Note: The translation has been provided in English. | The modifications were made in order to better illustrate the anatomy of the organ to patients or students, according to the criteria of the radiologist or specialist. In some cases, it was done to ensure the physical integrity of the model (minimum wall thickness) or to ensure the assemblability (separation of parts). |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME12 | Design and Manufacture with 3D printing, Anatomical models for teaching | They graphically designed 3D meshes or modified imported data from cross-sectional images to develop physical models specifically for teaching complex segments and branches of anatomy. 3D printing itself is easily accessible through online commercial services, and the models are made of polyamide or plaster. | Anatomical models of the liver, lungs, prostate, coronary arteries, and the Circle of Willis were created. These models have advantages that include customizable details, relative low cost, complete control of design focused on subsegments, potential for color coding, and the use of cross-sectional images combined with graphic design. | The radiologists have the opportunity to serve as leaders in medical education and clinical care with 3D printed models that provide beneficial interaction with patients, physicians, and learners in all specialties, proactively assuming the role of educator. Complex models can be developed to demonstrate normal anatomy or common pathology for medical education purposes. There is a need for randomized trials, which radiologists can design, to demonstrate the utility and effectiveness of 3D printed models for teaching simple and complex anatomy, simulating interventions, measuring patient satisfaction, and improving clinical care. | Simulator size | The size should facilitate didactics and mechanical resistance but also reduce cost. | The final size was a combination of the original model size plus modification to achieve the required price, and the wall thickness to ensure structural safety of the model. | Combination of numerical cost criteria and manufacturer expertise to define the minimum wall thickness. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME12 | Design and Manufacture with 3D printing, Anatomical models for teaching | They graphically designed 3D meshes or modified imported data from cross-sectional images to develop physical models specifically for teaching complex segments and branches of anatomy. 3D printing itself is easily accessible through online commercial services, and the models are made of polyamide or plaster. | Anatomical models of the liver, lungs, prostate, coronary arteries, and the Circle of Willis were created. These models have advantages that include customizable details, relative low cost, complete control of design focused on subsegments, potential for color coding, and the use of cross-sectional images combined with graphic design. | The radiologists have the opportunity to serve as leaders in medical education and clinical care with 3D printed models that provide beneficial interaction with patients, physicians, and learners in all specialties, proactively assuming the role of educator. Complex models can be developed to demonstrate normal anatomy or common pathology for medical education purposes. There is a need for randomized trials, which radiologists can design, to demonstrate the utility and effectiveness of 3D printed models for teaching simple and complex anatomy, simulating interventions, measuring patient satisfaction, and improving clinical care. | Simulator Configuration | In some cases, the organ had to be subdivided or manufactured in parts, so that the assembly and disassembly facilitate the illustration of the concepts and parts of the organ, including the use of marker paint or spray to further facilitate the didactics of the simulator. | Section the virtual model before proceeding to manufacture | Ease of didactics, according to the criteria of a radiologist or specialist. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME12 | Design and Manufacture with 3D printing, Anatomical models for teaching | They graphically designed 3D meshes or modified imported data from cross-sectional images to develop physical models specifically for teaching complex segments and branches of anatomy. 3D printing itself is easily accessible through online commercial services, and the models are made of polyamide or plaster. | Anatomical models of the liver, lungs, prostate, coronary arteries, and the Circle of Willis were created. These models have advantages that include customizable details, relative low cost, complete control of design focused on subsegments, potential for color coding, and the use of cross-sectional images combined with graphic design. | The radiologists have the opportunity to serve as leaders in medical education and clinical care with 3D printed models that provide beneficial interaction with patients, physicians, and learners in all specialties, proactively assuming the role of educator. Complex models can be developed to demonstrate normal anatomy or common pathology for medical education purposes. There is a need for randomized trials, which radiologists can design, to demonstrate the utility and effectiveness of 3D printed models for teaching simple and complex anatomy, simulating interventions, measuring patient satisfaction, and improving clinical care. | Simulator Price | It should be economical enough to compete with similar anatomical models. | Select scale according to search price formula and current model price. | Use of formula to choose scale (scale = (desired price / current price) ^ 1/3), The cost of each model depends on the size and amount of material used, with a total cost of each model ranging approximately between $40 and $100. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME12 | Design and Manufacture with 3D printing, Anatomical models for teaching | They graphically designed 3D meshes or modified imported data from cross-sectional images to develop physical models specifically for teaching complex segments and branches of anatomy. 3D printing itself is easily accessible through online commercial services, and the models are made of polyamide or plaster. | Anatomical models of the liver, lungs, prostate, coronary arteries, and the Circle of Willis were created. These models have advantages that include customizable details, relative low cost, complete control of design focused on subsegments, potential for color coding, and the use of cross-sectional images combined with graphic design. | The radiologists have the opportunity to serve as leaders in medical education and clinical care with 3D printed models that provide beneficial interaction with patients, physicians, and learners in all specialties, proactively assuming the role of educator. Complex models can be developed to demonstrate normal anatomy or common pathology for medical education purposes. There is a need for randomized trials, which radiologists can design, to demonstrate the utility and effectiveness of 3D printed models for teaching simple and complex anatomy, simulating interventions, measuring patient satisfaction, and improving clinical care. | structural integrity of the simulator | The minimum wall thickness must be large enough to ensure the structural integrity of the model | Select wall size at the discretion or suggestion of the manufacturer. | Select minimum wall thickness at the discretion of the manufacturer. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Simulator material | The simulator material must resemble the real tissues that will be intervened | Vascular System and Aneurysm: Shore A 27 hardness photopolymer material (Objet500 Connex 3D printer), translucent whitish vascular models were immersed in a red dye bath. Skull: printed composite material (zPrinter 650). Brain: a silicone (Dragon Skin, Smooth-On Inc., Macungie PA) with a lower elastic modulus than the mold, then mixed according to the manufacturer's instructions with a pigment additive (Silc Pig, Smooth-On Inc., Macungie PA). A touch mutator (Slacker, Smooth-On Inc., Macungie PA) further reduced the elastic modulus. | Vascular System: manufacturer's technical specifications for material hardness Soft material that simulates soft tissues. Skull: Drilling tests are performed by specialists. Brain: Additives are added to lower the elastic modulus. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Simulator Geometry | The geometry should be as close as possible to that of a real and average patient. | Aneurysm: From 9 sets of patient data from computed tomography angiography were imported to Mimics (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium), a medical reconstruction software package, the process of dividing an image into parts, was performed to isolate the geometries of aneurysmal and parental vessels, synthesized into a single computational model of the Circle of Willis, develops the hollow feature of the vessel core; Brain: the magnetic resonance imaging data set of a healthy patient was imported into Mimics and segmented, the resulting surface mesh was then imported into Geomagics, where partitioning facilitated the extraction of brain components to adjust or replace brain aneurysms without dismantling the entire simulation. Skull: A computed tomography data set, from a patient with normal cranial morphology, was imported into Mimics and segmented. | Simulate the real experience |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Material of Models for Mold | These materials will be used for the manufacture of the Mold. It does not require special load resistance qualities except for the curing temperatures during mold manufacturing, the most desirable quality is dimensional accuracy to replicate the patient's members. | Brain model: A Stratasys Dimension 1200es 3D printer (Eden Prairie, Minnesota, USA) was used to print the final computational models in acrylonitrile butadiene styrene plastic. The surface underwent partial chemical dissolution with a 90:10 volume solution of xylene and acetone to remove visible streaks created during the 3D printing process. | |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Geometry of Models for mold | It should be in the specific shape and size customized for the patient (bone tomography). | Brain model: The magnetic resonance imaging data of a healthy patient was imported into Mimics and segmented. The resulting surface mesh was then imported into Geomagics, where it was partitioned. The partitioning facilitated the operation of the simulator in extracting the brain, components to adjust or replace brain aneurysms without dismantling the entire setup. The mesh consists of 6 separable components: 1) the left frontal and parietal lobes, 2) the right frontal and parietal lobes, 3) the left temporal and occipital lobes, 4) the right occipital and temporal lobes, 5) the cerebellum, and 6) the brainstem (with a truncated portion of the optic nerves). | Simulate the real experience |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Geometry of the Mold | The geometry should be as close as possible to that of a real and average patient. | Brain Model: It was used to print the final computational models in acrylonitrile butadiene styrene plastic. The surface underwent partial chemical dissolution with a 90:10 volume solution of xylene and acetone to remove visible streaks created during the 3D printing process. A 2-part mold was created around each solid component of the brain using commercially available casting silicone (Mold Star [Smooth-On, Easton, Pennsylvania, United States]). These mold parts defined the negative shape of the intended brain. | Simulate the real experience |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Mold Material | The material must guarantee the geometry of the simulator and facilitate demolding. | A two-part mold was created around each solid component of the brain using a commercially available casting silicone (Mold Star [Smooth-On, Easton, Pennsylvania, United States]). These mold parts defined the negative shape of the intended brain. | Ease of manufacturing and physical integrity during successive demolding operations |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Simulator Configuration | The design must be modular. It must be subdivided to facilitate assembly and disassembly, the insertion of elements for academic study of different types of aneurysms, and maintenance by changing spare parts without implying the destruction of the entire simulator, and reducing maintenance costs. | Section the virtual model before proceeding to manufacture | Ease of teaching and maintenance |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Simulator Price | It should be economical enough during operation and maintenance. | Section the virtual model before proceeding to manufacture, the vascular model is modular. | A modular design was developed, following functional academic and maintenance cost criteria. Although the entire simulation costs less than $1000 for initial manufacturing, modular constructions allow for lower cost (less than $10 material cost) replacement of worn parts and enable the insertion of a specific aneurysm to fit specific teaching objectives. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | structural integrity of the simulator | The size of smaller details is limited by the machine's limits, 1mm | It was decided not to manufacture details of vessels and minor nerves less than 1mm, as well as not to manufacture the arachnoid membrane that covers the brain. | According to the manufacturer's criteria and machine limitations. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Surgical simulators | ME13 | The authors developed a manual, and a dimensionally accurate model for aneurysm clipping using patient-derived anatomical data and three-dimensional (3D) printing. The model design focused on reproducibility as well as adaptability to the patient's new geometry. | A modular, reproducible, and patient-derived medical simulation was developed for medical students to practice aneurysm clipping procedures. Various forms of 3D printing were used to develop an accurate geometry of the skull and vascular tree with 9 patient-derived aneurysms using 3D printing in conjunction with elastomers. Molding was utilized to achieve a patient-derived brain model with tactile properties not yet available in the market for 3D printing technology. An educational pilot study was conducted to measure the effectiveness of the simulation. | Through the innovative manufacturing process, a patient-derived simulator was developed for neurovascular surgical simulation. A qualitative follow-up study suggests potential for improving current educational programs; evaluations support the effectiveness of the simulator. | The proposed aneurysm clipping simulator has the potential to enhance learning experiences in the surgical environment. 3D printing and elastomeric molding can produce patient-derived models for learning in a dynamic environment that adds value to surgical training and preparation. | Functionality test | Professionals related must test the simulator and provide feedback with their opinion. | To qualitatively validate the simulation, 14 neurosurgery residents interacted with the simulation under the guidance of a neurosurgeon and provided qualitative feedback on its form and function. The evaluation covered the realism of the simulation when interacting with surgical tools (e.g., a bone drill) and medical devices (e.g., vascular clips). A simple survey assessing the clinical applicability, realism, and educational value of the simulation was completed by medical professionals. The survey consisted of 7 questions, and ratings were given on a 5-point Likert scale. | Fourteen residents of neurosurgery, with an average postgraduate year of 3.3 (i.e., range, 1-6 years), performed the Orbitozygomatic and Conventional Craniotomies for the first time on the skull model. Aneurysm clips were applied to occlude the aneurysms, including in the vascular model. The average response for all survey questions was greater than 4 (range 4.1-4.6) on the 5-point scale. The simulator is clinically applicable 4.4 (response range: 1 to 5, 1 strongly negative, 5 strongly positive), improved understanding of the aneurysm with respect to the parent artery 4.4, improved understanding of surgical vision 4.5, the application of the clip seemed realistic 4.1, bone drilling seemed realistic 4.1, the simulator was useful 4.6, and believed that surgical skills can improve with practice with the simulator 4.4. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | Simulator material | The simulator material must resemble the real tissues that will be intervened | Synthetic gelatin as a tactically realistic material for casting, widely used as a simulating fabric, synthetic gelatin is transparent, storage-stable gelatin that is mechanically identical to classic organic 10% gelatin, a mixture of 1000 g of gelatin and 9000 ml of water. With a density of 1060 kg/m3, synthetic gelatin has a similar density to most soft biological tissues. With a rigidity of the order of 10 kPa, it is 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printable materials and only one order of magnitude stiffer than brain tissue. The cost of the gelatin model material is $22, the gelatin can be reused by melting and molding, and creating the gelatin model requires 3 hours. | Soft material that simulates soft tissues, After probing a selection of suitable organic and synthetic materials regarding their structural integrity, rigidity, and cutting properties. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | Geometry simulator | The geometry should be as close as possible to that of a real and average patient. | Magnetic resonance images of a healthy 25-year-old woman. FreeSurfer (an image analysis tool that is documented and freely available online) was used to calculate brain volume, surface area, cortical thickness, and gyrification indices, and to create stereolithography files of the left and right brain hemispheres. Creating the brain surface model is free of charge and takes approximately 4 hours, fully automated, on a standard desktop computer. | Simulate the real experience |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | Material of Models for Mold | These materials will be used for the manufacture of the Mold. It does not require special load resistance qualities except for the curing temperatures during mold manufacturing, the most desirable quality is dimensional precision to replicate the patient's members. | They were 3D printed on a FlashForge Creator Pro Dual Extrusion 3D printer (FlashForge, City of Industry, California, USA) using acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) thermoplastic with a filament diameter of 1.75 ± 0.05 mm and filament roundness of 0.07 mm (GizmoDorks, Temple City, California, USA). The current price of the 3D printer is $900, plastic filament costs approximately $4 per hemisphere, and the 3D printing process takes 10 hours, without supervision. | |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | Geometry of Models for mold | The implant and bone tissue must be of the specific shape and size customized for the patient (bone tomography) | Computed Tomography of Patient / Dicom Postprocessed in meshmixer, Solidwork, simplify3d | Simulate the real experience |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | Geometry of the Mold | The geometry should be as close as possible to that of a real and average patient. | It was printed on a 3D brain model that was used as a template in a molding process. | Simulate the real experience |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | Mold Material | The material must guarantee the geometry of the simulator and facilitate demolding. | To create a realistic and deformable tactile brain model, a 3D brain model was printed and used as a template in a molding process. Flexible molds were created using Rebound 25 (Smooth-On, Macungie, Pennsylvania, USA), a Shore 25 hardness silicone with a tensile strength of 700 kPa, along with Plasti-Paste II (Smooth-On), a mother mold to maintain structural integrity. The mixture was brushed onto the left and right hemispheres in 4 layers to create a strong and durable mold for casting. The cost of the silicone mold material is $20, and its creation takes approximately 7 hours. | Ease of manufacturing and physical integrity during successive demolding operations |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | Simulator Price | Prices should be considered at each stage of manufacturing, including prices. | Prices are accounted for at each stage of manufacturing, as well as the times. | Creating the brain surface model is free of charge and takes approximately 4 hours, completely automated, on a standard desktop computer. using acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) thermoplastic with a filament diameter of 1.75 ± 0.05 mm and filament roundness of 0.07 mm (GizmoDorks, Temple City, California, USA). The current price of the 3D printer is $900, plastic filament costs approximately $4 per hemisphere, and the 3D printing process takes 10 hours, unsupervised. The material cost for the silicone mold is $20, and its creation takes approximately 7 hours. The material cost for the gelatin model is $22, the gelatin can be reused through melting and molding, and the creation of the gelatin model requires 3 hours. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | structural integrity of the simulator | The size of smaller details is limited by the machine's limits, 1mm | To characterize the mechanical properties of the gelatin model, 3 nanoindentation tests were performed on 5 mm thick brain slice models and compared to similar nanoindentation tests on sagittal slices of mammalian brains. To quantify potential mechanical degradation of the model, fresh brain slices were tested and compared to slices tested 3 months after fabrication. | In nanoindentation tests, the gelatin model conceptually exhibits characteristics similar to mammalian brain: it behaved like an ultra-soft and viscoelastic polymer. With a stiffness of E = 25.29+/-2.68 kPa, the cuts of the brain model (right) were less than an order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain slices (left) with a stiffness of E = 2.64+/-0.40 kPa. The shape of the indentation curve of the substitute material closely mimicked the rheology of mammalian brain tissue: both curves show a straight loading curve, a drop in force at constant deformation characteristic of viscous relaxation, a slightly concave upward discharge curve, and a negative force at the end of discharge characteristic of soft adhesion between the probe and the penetration tip. The mechanical properties of the brain model only moderately changed over time: with a stiffness of E = 27.64+/-0.37 kPa, the slices of new models were slightly stiffer than a 3-month-old model with a stiffness of E = 22.93+/-1.08 kPa but otherwise showed similar rheology. |

| GME1 | Biomodels for education and simulation | Biomodels | ME14 | In this technical note, the authors present a new technology for creating deformable and personalized models of the human brain. | The method combines 3D printing, molding, and casting to create a realistic physiological, anatomically based tactile model from magnetic resonance imaging images. Created from soft silicone, the model is easy to produce, cost-effective, durable, and several orders of magnitude softer than conventionally printed 3D models. The custom brain cost $50 USD and took 24 hours to manufacture. | In mechanical tests, the stiffness of the model (E=25.29+/-2.68 kPa) was 5 orders of magnitude softer than common 3D printed materials, and less than one order of magnitude stiffer than mammalian brain tissue (E=2.64+/-0.40 kPa). In a multicenter surgical survey, the size of the model (100.00%), visual appearance (83.33%), and surgical anatomy (81.25%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95.00%). | With minor refinements, Deformable custom brain models created through 3D printing enhance surgical training and preoperative planning with the ultimate goal of providing high precision, customization, and accuracy. | Functionality test | Professionals related must test the simulator and provide feedback with their opinion. | To characterize the functional features of the model, the deformable gelatin model was evaluated by 10 neurosurgeons and residents from King's College London, University of Oxford, and Stanford University. The surgeons were asked to evaluate the model and its usefulness as a training and neurosurgical planning tool. | Feedback surveys from 10 neurosurgeons and residents revealed overall satisfaction with the model and a wide range of potential uses. Surgical satisfaction with the model's rigidity (43.75%), cutting properties (43.75%), and haptic feedback (56.25%) could still be improved, while anatomy (81.25%), visual appearance (83.33%), and model size (100%) were perceived as very realistic. The model was perceived as very useful for patient illustration (85.00%), teaching (94.44%), learning (100.00%), surgical training (95.00%), and preoperative planning (95%). All surgeons responded that they would actively use the model for one or more of these purposes (100%). The survey suggests that the model will be highly useful for training and planning surgical procedures, including, among others, tumor removal (70%), aneurysm treatment (70%), fissure dissection (20%), and electrode placement (10%). The model could be anatomically improved by including vasculature (60%), ventricles (40%), individual tumors (30%), fissures (20%), brainstem (10%), arachnoid (10%), and cerebrospinal fluid (10%). By using different colors for different regions of the brain, the model could also be visually enhanced (20%). The overall response was very positive based on the justification that only a few training and surgical planning tools are currently available, and none of them have realistic tactile touch and mechanical properties. |

| GME2 | Surgical planning biomodels | Biomodels | ME18 | Explore the effect of 3D printing-assisted cognitive fusion on improving the positive rate of prostate biopsy. | From August to December 2014, 16 patients with suspected prostate lesions were detected by multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and included in the study. Prostate biopsy was performed using 3D models of prostate reconstruction, computer-simulated biopsy, 3D printing, and cognitive fusion biopsy. All patients had received multiparametric 3.0 T magnetic resonance imaging before the biopsy. The MRI DICOM files were imported using medical imaging software for 3D reconstruction modeling to generate a printable stl file for 3D printing, using transparent resin as the raw material. A biopsy of 2 to 3 cores was performed with suspected lesions detected on magnetic resonance imaging. | For the 16 patients in the present study, 3D modeling with fusion-based cognitive targeting biopsy was successful. For a single patient, 1-2 lesions (average: 1.1 lesions) were discovered, followed by 2-6 cores (average: 2.4 cores) added as target biopsy. Systematic biopsies represented a total of 192 cores, with a positive rate of 22.4%; targeted biopsies represented a total of 39 cores, with a positive rate of 46.2%. Among these cases, 10 patients (62.5%) were diagnosed with prostate adenocarcinoma, in which seven were discovered by systematic and targeted biopsy, one was diagnosed by systematic biopsy only, and two were diagnosed by targeted biopsy only. For systematic biopsy, the Gleason score ranged from 6 to 8 (average: 7), while for targeted biopsy, it ranged from 6 to 9 (average: 7.67). Among the seven patients who were diagnosed by systematic and targeted biopsy, three (42.8%) were reported with a higher Gleason score in the targeted therapy than in the systematic biopsy. | The 3D printing technique was applied to aid cognitive fusion in the early diagnosis of prostate cancer, which significantly improved the positive biopsy rate and avoided misdiagnosis of high-risk prostate cancer. This technique proves to be easy and simple. The increased effort in targeted biopsy does not increase the incidence of complications. Its application and popularization will surely benefit more patients on a larger scale in the future. | Simulator material | The material application can intuitively show the location, size, and morphology of the tumor. | Transparent resin material used for 3D printing model, tumor's spatial structure. | Before the biopsy, the operator can observe a 3D model of the tumor from multiple angles, thus evaluating the possibility of sampling by systematic biopsy or cognitive fusion. |

| GME2 | Surgical planning biomodels | Biomodels | ME18 | Explore the effect of 3D printing-assisted cognitive fusion on improving the positive rate of prostate biopsy. | From August to December 2014, 16 patients with suspected prostate lesions were detected by multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and included in the study. Prostate biopsy was performed using 3D models of prostate reconstruction, computer-simulated biopsy, 3D printing, and cognitive fusion biopsy. All patients had received multiparametric 3.0 T magnetic resonance imaging before the biopsy. The MRI DICOM files were imported using medical imaging software for 3D reconstruction modeling to generate a printable stl file for 3D printing, using transparent resin as the raw material. A biopsy of 2 to 3 cores was performed with suspected lesions detected on magnetic resonance imaging. | For the 16 patients in the present study, 3D modeling with fusion-based cognitive targeting biopsy was successful. For a single patient, 1-2 lesions (average: 1.1 lesions) were discovered, followed by 2-6 cores (average: 2.4 cores) added as target biopsy. Systematic biopsies represented a total of 192 cores, with a positive rate of 22.4%; targeted biopsies represented a total of 39 cores, with a positive rate of 46.2%. Among these cases, 10 patients (62.5%) were diagnosed with prostate adenocarcinoma, in which seven were discovered by systematic and targeted biopsy, one was diagnosed by systematic biopsy only, and two were diagnosed by targeted biopsy only. For systematic biopsy, the Gleason score ranged from 6 to 8 (average: 7), while for targeted biopsy, it ranged from 6 to 9 (average: 7.67). Among the seven patients who were diagnosed by systematic and targeted biopsy, three (42.8%) were reported with a higher Gleason score in the targeted therapy than in the systematic biopsy. | The 3D printing technique was applied to aid cognitive fusion in the early diagnosis of prostate cancer, which significantly improved the positive biopsy rate and avoided misdiagnosis of high-risk prostate cancer. This technique proves to be easy and simple. The increased effort in targeted biopsy does not increase the incidence of complications. Its application and popularization will surely benefit more patients on a larger scale in the future. | Simulator Geometry | The translated value of the provided data La geometría debe ser la de del paciente especifico in English is The geometry should be that of the specific patient. | All patients had received a multiparametric 3.0 T magnetic resonance imaging (Siemens Magnetom Skyra, Germany) before the biopsy. The scanning sequence included T1-weighted, T2-weighted, DCE, and DWI. | The prostate is a soft tissue organ, so processing MRI data images is more difficult than that of bones, teeth, and other tissues. In the data modeling phase, a lot of recognition of pelvic anatomy is required, with the help of imaging professionals. Therefore, based on various multiparametric magnetic resonance fusions, targeted biopsy cannot completely replace systematic biopsy. The development of targeted biopsy is based on more sensitive advances and specific imaging technologies. |