Database for Process Chain with FFF

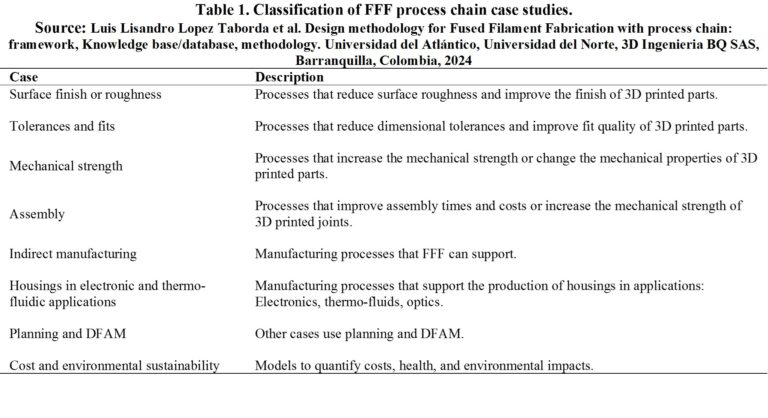

Table 1 summarizes the classification and description of the FFF process chain cases that were found during the case analysis of the research

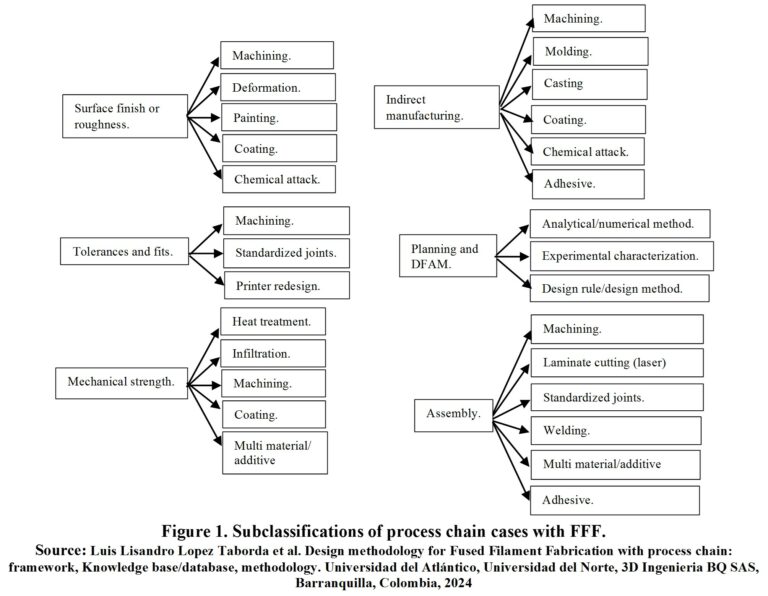

Figure 1 summarizes the FFF process chain case subclassifications obtained from the previous table and during the analysis of cases. Figure 1 excludes the cost and sustainability case as it applies to all other cases. Housing cases are omitted as they encompass the same processes as indirect manufacturing and assembly. While not explicitly stated, each case includes planning and DFAM, which involves manufacturing and design planning based on design rules, theoretical-numerical methods, or experimental characterizations.

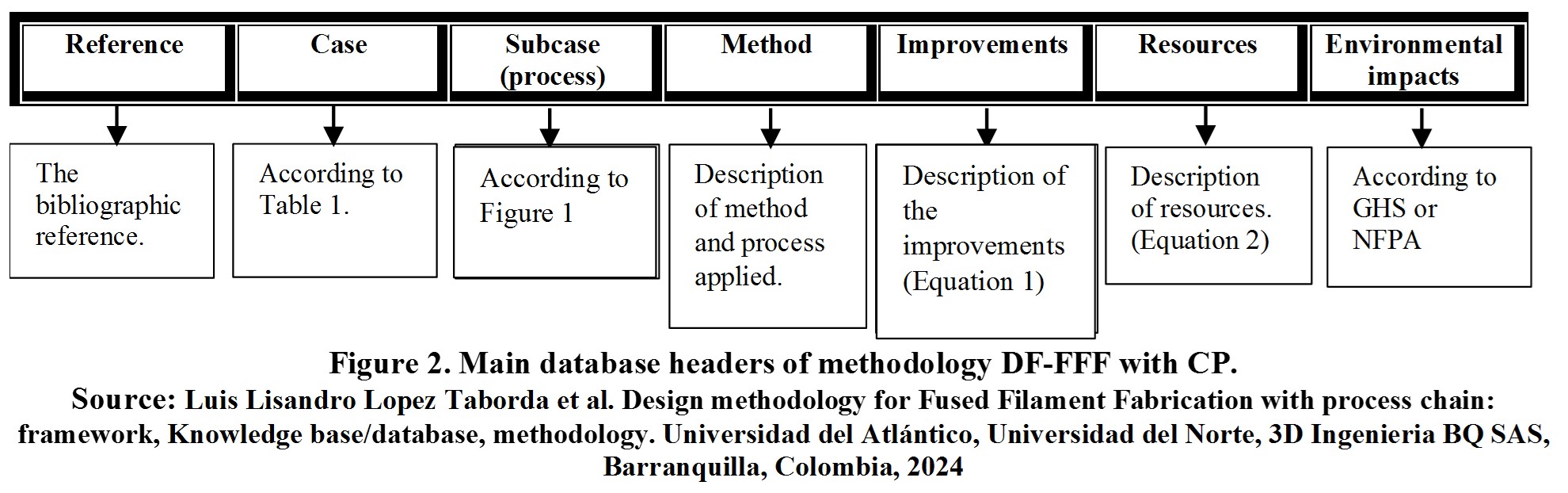

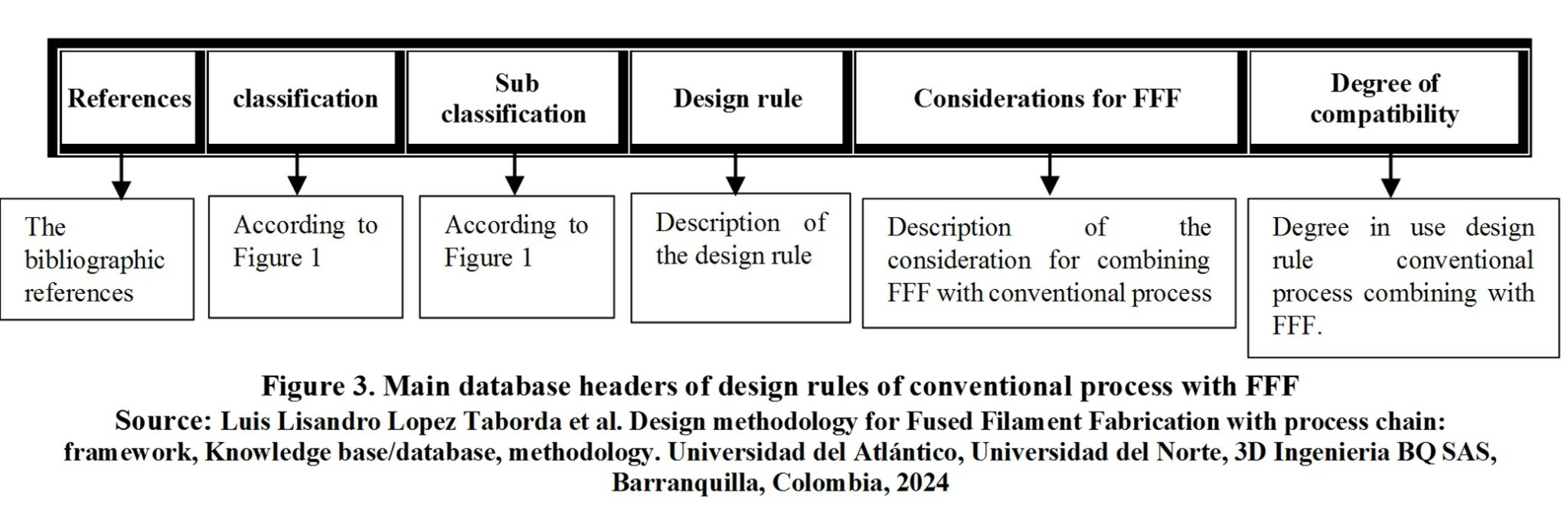

Figure 2 summarizes the main headings of the database.

Below is a detailed explanation of each heading in Figure 2.

- Reference: Contains the bibliographic reference analyzed to generate specific and general guidelines.

- Case:One (1) of the eight (8) cases in Table 1 in which the analyzed reference can be classified.

- Subcase:Some of the specific process or sub-cases in Figure 1, depending on the case to which the reference belongs.

- Method: Description step-by-step for combining conventional manufacturing processes with FFF.

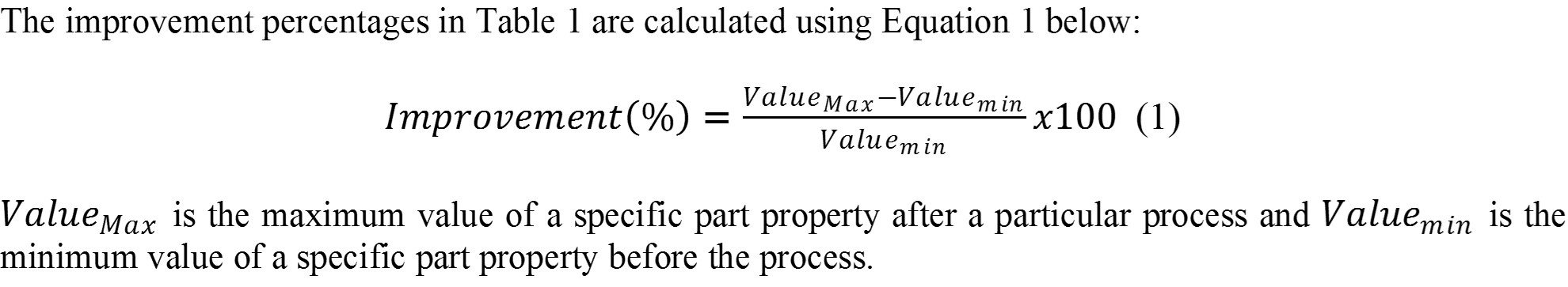

- Improvements: It is a percentage improvement obtained in the property of an FFF part by combining it with a conventional manufacturing process.

- Resources: Describes additional materials and conventional machinery needed for combining FFF with conventional manufacturing, including associated time, costs, and licenses

The service costs include machinery depreciation, energy consumption, depreciation of computers and software licenses with their energy consumption and internet service, and skilled labor.

- Environmental Impacts: Describes health and environmental hazards of extra materials based on GHS and NFPA scales, incorporating measures for prevention and management as per material safety data sheets.

Under each heading or column is the respective information, and each row contains information related to a specific case or reference. The purpose is to search according to the desired case to apply the guidelines of other cases to one’s case. In case of detailed information, the reference can be consulted directly.

Process Chain

| Group | Requirement | Secondary process | References | Objective | Method | Results and conclusions | printer, machines | brand | material | characterization | parameters | parameter values | Observation and suggestions | Additional resources required (materials, software, costs and time) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness, tolerances and fits, mechanical strength | Experimental characterization, analytical computer tool | S11 | The purpose of this document is to examine the various preprocessing and postprocessing approaches used to enhance the surface characteristics of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) prototypes based on the fused deposition modeling (FDM) method. | The consequences and scope of the pre-processing and post-processing parameters of FDM have been studied independently. The comprehensive study includes the domain, limitations, validity, and scope of various techniques adopted to improve the surface characteristics of ABS parts. Replicas of hip implants are manufactured by maintaining the reviewed optimal pre-processing parameters, and a case study has been conducted to evaluate the capability of the steam smoothing process to enhance surface finish. | Process parameter optimization: * Manufacturing orientation, manufacturing with a 0° angle (horizontal) produces the maximum surface performance. In most studies, orientation angles of 0° (horizontal) and 90° (vertical) were considered more effective for surface finishing, cost, and manufacturing time. Construction angles between 40° and 60° reduced surface finishing and increased cost, as maximum support material was used due to the model's inclination. Some authors observed that a 30° orientation angle is the most effective for surface finishing and mechanical properties, such as flexural and impact strength, using Grey Taguchi optimization techniques. The horizontal surface has better surface finishing than the vertical surface and worse for circular shapes due to the formation of elliptical curves on the descending surface of the layer junction. Most experimental characterizations and optimizations employ standard square and rectangular models by orienting them at different angles. The problem arises when real parts with intricate shapes and intricate details need to be manufactured. * Decreasing the nozzle diameter and layer height reduces the staircase effect defect but increases construction times and cost. There is a minimum layer thickness beyond which it cannot be decreased, subject to the printer's minimum resolution and nozzle diameter. * The minimum width of the road resulted in maximum surface finishing and dimensional accuracy. It has been noted that narrower widths of roads also improved the mechanical properties of FDM parts. * Wider contour (perimeter) width is better for surface finishing and dimensional accuracy, as thin contours are easily deformed by the heat generated during extrusion. * Surface finishing generally increases with negative and positive air gaps, while minimum surface finishing and dimensional accuracy occur with zero air gaps. * The best surface finishing was obtained with a 0° frame angle and the worst with 60°, while the frame angle of 45° was optimized for the best surface finishing and 0° for the best dimensional accuracy using an optimization algorithm. Others concluded that the 45°/45 frame angle style provides the maximum surface finishing. Additionally, a 30° frame angle provides maximum flexural and impact strength. The variation in interpretations by different authors may be due to differences in CAD models and other parameters. * Higher temperature produces a smooth surface due to delayed solidification. The model temperature is the third most important factor affecting the surface after layer thickness and orientation angle. Below 80°C, there was less plastic adhesion to the build plate, while dimensional accuracy decreased above 100°C. Higher temperature leads to good surface finishing but poor dimensional accuracy. Slicing: * Adaptive slicing, the maximum cusp height limit is specified by the user, and therefore the algorithm automatically slices the CAD within a given range. This method imposes constraints on surface roughness and cusp height uniformly across the entire surface of the part. Adaptive slicing is based on the region where the user can vary surface roughness in different places on the part's surface according to their needs. There are few limitations in the techniques mentioned above, such as complexities and errors in tessellated CAD files. * Direct slicing, the slicing software directly slices the CAD without conversion to .stl, which is accurate, fast, and requires less storage memory. However, there is a difficulty as the CAD model is stored as mathematical definitions and analytical surface instead of points and coordinates, requiring software and hardware development to implement curved layer slicing algorithms with the aim of improving both mechanical properties and surface finishing of FDM parts. Additionally, surface finishing can only be improved to a certain level, depending on the hardware and software, which is unacceptable for using FDM parts for precision rapid machining. | FFF, FDM, process parameter optimization, slicing optimization | - | ABS | Roughness Ra, dimensional deviation or dimensional tolerance, mechanical resistance. | Optimization of process parameters: Print orientation (OI), nozzle diameter (d), layer height (t), layer width or pattern (w), airgap or % (AG), pattern orientation (OT), print temperature (TI), bed temperature (TC); slicing optimization: adaptive slicing (variation of cutting by zone), direct cutting (direct slicing without stl conversion). | Optimization process parameters: OI: 0, 30, 60, 90°; airgap or % (AG or %: +, -, 0.0mm), OT: 0, 30, 60, 45, 90, TC: 80, 100; | Increase print temperature, keep bed temperature between 80 to 100°C. Orient the piece at 0° (horizontal) and 90° (vertical) except for curved surfaces. Avoid orientations that generate support. Use a 0° or 45° pattern orientation. Use 100% infill percentages or 0.0mm airgap. Minimize layer height, nozzle diameter, and line width to improve finish but at the expense of manufacturing times and costs. Increase line width on the contour or perimeter. Use slicing programs that include adaptive cutting and discretize layer height by piece zone as needed. | adaptive slicing program: *Simplify 3D at $149 USD permanent license (https://www.simplify3d.com/software/release-notes/version-4-1-0/ consulted on March 29, 2021), *Slic3r at $0 USD (https://slic3r.org/ consulted on 29/03/2021), *CURA Ultimaker at $0 USD free version, $300 USD light license per year, $720 USD standard license per year, $3600 USD advanced license per year (https://ultimaker.com/en/software/ultimaker-cura consulted on 29/03/2021), *IdeaMaker Raise 3D at $0 USD (https://www.raise3d.com/ideamaker/ consulted on 29/03/2021) |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness, tolerances and fits, mechanical strength | Machining, Deformation | S11 | The purpose of this document is to examine the various preprocessing and postprocessing approaches used to enhance the surface characteristics of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) prototypes based on the fused deposition modeling (FDM) method. | The consequences and scope of pre-processing and post-processing parameters of FDM have been studied independently. The comprehensive study includes the domain, limitations, validity, and scope of various techniques adopted to improve the surface characteristics of ABS parts. | Mechanical finishing: *Manual sanding, Being simple and economical, manual methods are not controlled, measured, consistent, and precise, and depend on the operator. *Abrasive grinding, it used the abrasive machining action of sandpapers of different grain sizes rotating on a wheel as a material removal process by chip formation. Faster feed rate and smaller media increased the material removal rate and improved surface hardness, implemented abrasive grinding using bulk laminar abrasive paper to achieve a 90% improvement in surface finish with very little deviation in dimensions. *Abrasive flow machining, a high-speed abrasive jet impacts the rough surface until it is smoothed, the pressure of the media, grain size, and flow time control the surface roughness, with a 70% improvement in surface roughness of plastic parts using dry air as the carrier and glass beads as the abrasive media. Uneven material removal is a disadvantage, which caused weight loss and a reduction of up to 5.85% in thickness, the process was very random and aggressive as it damaged edges and corners. *Sandblasting, improvements of up to 96% in surface roughness. Sandblasting has been recommended by Stratasys for post-vapor smoothing and has proven to be an ultra-fine finishing process. *Vibratory bowl finishing, abrasives mixed with water through a vibratory mass spring system, different material removal rates are achieved depending on time, size, shape, weight, and compound of the media, with an increase of 31.67% and 4.59% in surface roughness and hardness, respectively, using a pyramidal-shaped media with longer machining times from 3h to 4h, it was found that machining for more hours and using a lower media weight provided better dimensional stability for ABS parts. *Barrel tumbling, parts are loaded into a closed rotating tube with an abrasive compound and water. The process requires low initial, operating, and maintenance costs and is capable of machining different geometries without using any fixtures, ceramic media of different geometries were used and a 52% decrease in surface roughness was reported with triangular media. Rotation speed, machining time, and shape and size of the media were found to be the main parameters controlling the material removal rate, they recognize that the orientation angle of FDM parts and the barrel finishing time are the most important parameters in the case of surface roughness and dimensional accuracy. The maximum material removal rate occurs at a 90° angle orientation while the minimum at 18°. *Hot cutting machining, the hybrid system has been proposed by integrating hot cutting with additive technique, the lay angle and cutting direction were the main influential parameters. *Ball polishing to press the surface peaks into the valleys, increased penetration depth and spindle speed improved surface finish and wear of ABS parts, while hardness increases with the force applied by the burnishing tool. *Mechanical methods present challenges with complex and intricate shapes. *The abrasive action of the media rounds sharp edges and corners and distorts the geometry and dimensional stability of the part. *Deeper surfaces within grooves, notches, or other recesses are more difficult to reach by abrasives. *They are quite inconsistent in imparting a uniform surface finish on all parts. | FFF, FDM, manual sanding, abrasive grinding or grinding, abrasive flow machining, sandblasting, vibratory bowl or tumbler, barrel deburring, ball polishing, hot machining | - | ABS | Roughness Ra, dimensional deviation or dimensional tolerance, hardness (ball finish) | Manual sanding; abrasive grinding or sanding (use of different sandpaper and a wheel); abrasive flow machining (pressure of the medium (dry air), grain size (glass beads), flow time); sandblasting; vibratory bowl (abrasives mixed with water, type of abrasive media (pyramidal), vibration time (3 to 4 hours)); hot machining; ball polishing (spindle speed, penetration depth, applied force); | Grinding or sanding (use of different sandpaper and a wheel); abrasive flow machining (dry air pressure, glass bead grain size, blasting time); vibratory bowl (abrasives mixed with water, type of abrasive media for example pyramid, vibration time of 3 to 4 hours); | *Manual sanding, Being simple and economical, manual methods are not controlled, measured, consistent, and precise. *Abrasive finishing techniques on plastic parts using sandblasting, barrel tumbling, centrifugal tumbling, vibratory bowl, and ultrasonic abrasion achieve an average improvement of 40%, 78%, 81%, 73%, and 60%, respectively, in surface finishing. *Abrasive finishing resulted in the removal of unwanted material from edges and corners due to the impact of abrasive media in these mass finishing processes. *Implemented abrasive grinding or sanding using bulk laminar abrasive paper to achieve a 90% improvement in surface finishing with very little deviation in dimensions. *Abrasive blasting, 70% improvement in surface roughness of plastic parts using dry air as a carrier and glass beads as abrasive media. It caused weight loss and a reduction of up to 5.85% in thickness, the process was very random and aggressive as it damaged edges and corners. *Sandblasting, improvements of up to 96% in surface roughness. *Finishing of vibratory bowl or vessel, with an increase of 31.67% and 4.59% in surface roughness and hardness, respectively, using a pyramid-shaped media with longer machining times from 3h to 4h. *Tumbling or barrel finishing, presents a 52% decrease in surface roughness with triangular media. The maximum material removal rate occurs at the 90° angle orientation while the minimum at 18°. *Mechanical methods present several challenges to complete complex and intricate shapes. The abrasive action of the media rounds sharp edges and corners and distorts the geometry and dimensional stability of the piece. Additionally, deeper surfaces within grooves, notches, or other indentations are harder to reach by abrasives. *Mass finishing methods are effective but are quite inconsistent in imparting a uniform surface finish on all parts. | *Lijado manual: sandpaper $3.17usd for 6 sandpapers of 93x228mm, number (grain size) 150-100-60 *Sand Blasting: Sandblasting gun or blasting from $22usd to $49.45 usd, 90-150 PSI compressor with a minimum of 4.0 CFM (recommendations according to sandblasting gun), 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 HP, from $170usd to $360usd, hose and couplings for compressor at $50 USD, sand for sandblasting at $10 USD for 25kg *Abrasive Jet Machining: Sandblasting gun or blasting from $22usd to $49.45 usd, 90-150 PSI compressor with a minimum of 4.0 CFM (recommendations according to glass bead supplier 20-60 PSI maximum at 70 PSI), 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 HP with a minimum of 4.0 CFM, from $170usd to $360usd (silent and oil-free, consulted on Amazon USA on 29/03/2021), hose and couplings for compressor at $50 USD, glass beads for blasting at $10 USD for 8lb, grain or mesh 100-170 *Abrasive Grinding or Grinding: 1/2 HP bench grinder with 6' diameter at $44.4 usd or 130Watt rotortool with kit including abrasive stone and sandpaper at $43 usd or 4x36 belt sander and 6 diameter disc with 1/2 HP at $255.4usd, 4x24 belt sandpaper grain 120 or 240 and 3 units at $4.2USD or sanding disc at $3.87USD. *Vibratory Tumbler: 0.05 cubic feet vibratory tumbler, 60hz, 115V at $100usd or 0.18 cubic feet vibratory tumbler, 304.8mm diameter x 106.7mm high, 60hz, 115V at $500usd, complete kit of medium rock for polishing with 4 different steps of 3.5 pounds at $38USD. *Barrel Tumbling or Boring: Rotary drum with a capacity of 3.3 liters (317.5mm length x 241.3mm diameter, approximate measurements), at $112USD, Rotary drum with a capacity of 7 liters (381mm length x 279.4mm diameter, approximate measurements) at $190USD, 5 lb bag of abrasive media of stainless steel cylinders with a diameter of 1.2mm x 6.47mm long at $42.95USD. *Hot Machining: CNC milling/engraving machine at $290-370USD, set of 10 1/4 carbide bits at $47USD, soldering iron at $20USD *Honing: CNC milling/engraving machine at $290-370USD, honing tool $40 usd (estimated based on cylinder honing) *Machines require energy resources and consumables for their operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs (prices consulted on Amazon USA and Mercado Libre Colombia from March to April 2021) |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness, tolerances and fits, mechanical strength | coating, chemical attack | S11 | The purpose of this document is to examine the various preprocessing and postprocessing approaches used to enhance the surface characteristics of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) prototypes based on the fused deposition modeling (FDM) method. | The consequences and scope of pre-processing and post-processing parameters of FDM have been studied independently. The comprehensive study includes the domain, limitations, validity, and scope of various techniques adopted to improve the surface characteristics of ABS parts. | Chemical finish: *Manual painting, saves time and costs, but manual methods are not uniform. *Acetone immersion, FDM parts are immersed in a solution of acetone (90% dimethyl ketone and 10% water) for a certain time. *Immersion of parts in an acetone solution for 5 minutes also improved flexural strength, tightness, and wear resistance, slightly reduced tensile strength, increased weight, ductility, and compressive strength, while a 1% shrinkage was recorded, concentration-temperature interaction and concentration-time interaction have the greatest impact on surface roughness. *It has been used for the surface finishing of ABS parts for biomedical device applications, the optimal conditions were exposure of 1 to 8 hours with a 60% aqueous solution to obtain the best surface finish (nanoscale) and preserve the characteristics of the parts. *It has been used for sealing and supporting liquid pressures of 276 kPA. *A fan has been used for forced circulation of acetone vapors in a closed chamber, improving the finish by increasing fan revolutions, while longer exposure is required for finishing ABS parts with larger surface area. *Cold vapors at 20°C have been used in a closed container to control rapid vapor-plastic interaction, improving the surface with minimal changes in dimensions up to a 40-minute exposure. However, with a longer duration of 90 minutes, corners and sharp edges are rounded. *Post-processing with acetone has been shown to be a highly effective, easy, fast, and economical surface finishing process, but there is a risk of eroding and dissolving small features of the parts over longer periods and using undiluted acetone, while using a diluted solution can prolong immersion time. Therefore, the method needs to be controlled, automated, and mechanized to carry out more precise and systematic finishing. *Smoothing with vapor, a technique has been developed in which the surface of the part is temporarily arched due to exposure to vapors produced by heating the chemical substance in a controlled environment. Initially, the parts are allowed to cool for a few minutes in the drying chamber and then placed in the smoothing chamber for 10 to 30 seconds. A fixed amount of solvent is heated in the smoothing chamber, and thus the vapors (chemicals) rise to deposit on the hanging ABS part through the surface and temporarily flatten it due to surface tension. After three cycles of vapor exposure, the parts were subjected to a sodium bicarbonate jet. Initial and final readings showed insignificant changes in dimensions with an extremely smooth surface. *Electroplating, wind tunnel models were manufactured using FDM to reduce cost and manufacturing times. Models used without surface finishing do not produce satisfactory results because a highly smooth surface is necessary for high-speed testing. Therefore, FDM parts are etched to clean the surface and then coated with palladium acting as an adhesive agent, finally, chromium is deposited providing the required durability. The thin layer of electroplated chromium on the FDM model improved surface finish, wear resistance, and mechanical strength. Aerodynamic test results showed that the chromium-coated model had good lift capacity compared to the uncoated model. In addition, the data showed very good agreement between the steel model and the coated FDM model within the Mach number range of 0.1 to 0.3. *Improvement in hardness, corrosion resistance, and tensile strength of copper-coated ABS plastics has also been reported. *Electrodeposition of FDM parts improved surface finish and tensile strength of parts with an increase in layer thickness. *Copper, nickel, and chromium coatings have been tested on ABS parts, which tend to increase impact strength and hardness in addition to improving surface finish with increasing coating layer thickness. *The major limitation of coating and electroplating is the added cost of the process and the limited field of applications. The method induces mechanical strength and hardness, but the dimensions of the parts are also altered due to the outer surface layer. *Metal coatings on ABS replicas can increase practical complications during coating castings for rapid tooling applications. *The application of reinforcing fluids such as water-based Epsom salt, wax, acrylic resin protektine, cyanoacrylate, etc., has the potential to reduce surface roughness and improve the mechanical properties of the parts. Increased tensile, compression, and flexural strength of 3D printed parts have been reported with exposure to polyurethane glue, cyanoacrylate, and Epsom salt. *Environmental conditions and construction orientation in plastic parts influence the effectiveness of reinforcements. | FFF, FDM, manual painting, acetone immersion | - | ABS | Roughness Ra, dimensional deviation or dimensional tolerance, mechanical resistance (immersion in acetone) | Manual painting; acetone immersion (acetone/water volume ratio, exposure time, forced convection, vapor or liquid temperature), steam smoothing (fixed liquid amount, temperature, cooling time, exposure time, number of cycles), electrodeposition (fixative type, coating element type, layer thickness). | Immersion of acetone (volumetric percentage: 60%, 90%, exposure time: from 1 to 8 hours, 5 minutes, 40 to 90 minutes), steam smoothing (cooling time: minutes, exposure time: 10 to 30 s; number of cycles: 3), electrodeposition (element: Cu, Ni, Cr, fixing element: palladium). | *Manual painting saves time and costs, but manual methods are not uniform. *Acetone immersion, in addition to improving surface finish, improved flexural strength, tightness (supports fluid pressure up to 246KPa), and wear resistance, slightly reduced tensile strength, increased weight, ductility, and compressive strength, while a 1% shrinkage was recorded. *In acetone immersion, concentration-temperature interaction and concentration-time interaction have the greatest impact on surface roughness. For example, for a 90% acetone solution, 10% dimethyl ketone, and 10% water, the optimal immersion time is 5 minutes. For another case, the optimal conditions were exposure of 1 to 8 hours with a 60% aqueous solution for a good finish without dimensional changes. A fan has been used for forced circulation of acetone vapors in a closed chamber, improving finish by increasing fan revolutions. Cold vapors at 20°C in a closed container have been used to control rapid vapor-plastic interaction, improving the surface with minimal dimensional changes up to a 40-minute exposure. Beyond 90 minutes, sharp corners and edges are rounded. *Post-processing with acetone has proven to be a highly effective, easy, fast, and economical surface finishing process, but there is a risk of eroding and dissolving small features of the parts over longer periods and using undiluted acetone. The use of a diluted solution can prolong immersion time, so the method needs to be controlled, automated, and mechanized to achieve a more precise and systematic finish. *Smoothing with vapor involves cooling the parts for a few minutes in the drying chamber and then placing them in the smoothing chamber for 10 to 30 seconds. A fixed amount of solvent is heated in the smoothing chamber, and the vapors (chemicals) rise to deposit on the ABS part hanging inside, penetrating through the surface and temporarily flattening it. After three exposure cycles, it is subjected to a sodium bicarbonate jet, improving the finish without significant dimensional changes. *Electrodeposition or electroplating (copper and/or nickel and/or chromium coating and fixation with palladium) increases wear resistance, mechanical strength, impact resistance, and hardness, in addition to improving surface finish with increased coating layer thickness, but the dimensions of the parts are also altered due to the coating on the outer surface. *The main limitation of coating and electroplating is the added cost of the process and the limited field of applications. *The application of reinforcing fluids such as water-based Epsom salt, wax, acrylic resin protektine, cyanoacrylate, etc., has the potential to reduce surface roughness and improve the mechanical properties of the parts. Environmental conditions and construction orientation in the mechanical properties of plastic parts influence the effectiveness of reinforcements. | *Manual painting: Spray paint (synthetic enamel) 400ml with coverage of 1.1m^2 in 2 coats and drying time of 20min at $2-3 USD, Polyurethane spray paint 400ml with coverage of 1.1m^2 and fast drying at $8-10 USD, Polyurethane paint 4000ml (4L) with coverage of 18m^2/L, with catalyst (ratio 4:1), and 6-hour pot life at $74-80 USD, Acrylic paint 250ml at $2-3 USD, Airbrush kit (1/6 HP compressor, hose, 22cm^3 container, nozzle, and gun) at $160-170 USD, Brush $1-3 USD. *Acetone immersion: Pure anhydrous acetone x 250ml at $8-10 USD, Pure acetone (nail polish remover) x 473ml at $10 USD. *Electrodeposition: Palladium adhesive element 28.4ml at $2656 USD (https://www.macrotrends.net/2542/palladium-prices-historical-chart-data consulted from March to April 2021), 10-gauge Copper wire x 7.6m at $18 USD, 26-gauge Copper wire x 30m at $8 USD, Copper sheet 152.4x152.4x1.016mm at $15 USD, Nickel strip 0.15x6x50mm x 50 units at $6 USD, Nickel strip roll 0.2x8mmx9.75m at $17 USD, Tin wire roll (99Sn-Ag0.3-Cu0.7) 1mm x 100g at $12 USD, Chromium grains x 1kg at $48 USD, pure chromium order from 1 to 999kg at $29 USD/kg, pure chromium order over 1000kg at $16 USD/kg (https://spanish.alibaba.com/product-detail/hrcr-good-price-pure-chrome-cr-metal-chromium-lumps-62019389951.html?spm=a2700.7724857.normal_offer.d_title.5c5e6214h12fCd&s=p), pure Silver grains 28.4ml at $45 USD, pure Silver ingot Lego piece type, 28.4ml at $50.2 USD, pure Silver ingot coin 2.8x5x0.3cm at $12 USD, 50cm cable with alligator clips, 20AWG at 8A x 10 units at $25 USD or 50cm cable with alligator clips, 22AWG x 5 units at $7 USD, Water or Distilled water, adjustable power supply 110/120V input to 0-30V output/0-10A at $70 USD or power supply 120V input to 0-15V output/0-2A at $45-50 USD, Hydrochloric acid or muriatic acid 1.5L at $1.8-2.0 USD (https://www.unionferretera.com/productos-limpieza-online/productos-quimicos-limpieza/aguafuerte-salfuman-15-litros.html), 250ml beaker flask $5-8 USD, 1000ml beaker flask at $14 USD, set of glass precipitate beakers 50, 100, and 250ml at $11 USD, set of beaker flasks 100, 250, 500, 1000ml at $20-30 USD. *Reinforcement fluid: Epsom salt x 8.618kg at $27 USD, Epsom salt 454g at $2-3 USD, Polyurethane sealer x 300ml at $6.57 USD, Polyurethane glue x 750ml at $3-4 USD, Waterproof polyurethane glue x 1000ml at $33 USD, Cyanoacrylate glue (super glue, loctite 681925) x 2ml x 6 units at $23 USD, Cyanoacrylate glue (super glue, loctite 1699233) x 4g x 6 units at $38 USD, Cyanoacrylate glue x 162ml at $24-26 USD, Liquid epoxy resin x 80g at $8-10 USD, Rigid epoxy resin (1:1 ratio) x 1000ml at $17-19 USD, Rigid epoxy resin (1:1 ratio) x 1kg x 840ml at $14-16 USD, XTC-3D epoxy resin (2:1 ratio) x 181ml x 181g at $25 USD. *Machines require energy resources and consumables for operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment, which increase costs. (If not indicated otherwise, prices are consulted on Amazon USA and Mercado Libre Colombia from March to April 2021) |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness | Chemical attack | S11 | Improve the surface characteristics of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) prototypes based on the fused deposition modeling (FDM) method. | Hip implant replicas are manufactured by maintaining the optimal preprocessing parameters reviewed, and a case study has been conducted to evaluate the capability of the steam smoothing process to improve surface finishing. | In the present study, a hip implant component is drawn through Solidworks (total length of 178mm and average diameter of 7mm, approximate measurements). The piece has been converted to stl through Catalyst Ex. Replicas of hip implants have been manufactured with ABS P400 at an orientation angle of 0, 90°, with a lattice orientation of 0/90°, at a temperature of 310°C, layer height of 0.254mm, and lattice width of 0.407mm, using the 'uPrint SE' printer. Cleaning and removal of the support structure in the ABS replicas is done using a liquid at 50°C for 30 minutes through an ultrasonic wave generator. The vapor smoothing apparatus used in the study is the Final Touch Smoothing Station Stratasys (200-240 Volts AC, 50/60 Hz, 20 amp, Decafluoropentane fluid (10-30%), Trans-Dichloroethylene (60-100%)), 20 liters of fluid, with an acetone chamber temperature of 65°C, chamber cooling temperature of 3°C, and smoothing chamber temperature of 48°C. The pre and post cooling times are 15 minutes each, the exposure times are 15, 30, 45 seconds, and the exposure cycles are 1, 2, and 3, with rest intervals between cycles of 24 hours. Among the results obtained, the improvement in Ra roughness was 90-94% (depending on the exposure time) in the first cycle, 34-42% in the second cycle, and 18-35% for the third cycle, with a total improvement of 95.73-97.72% after the 3rd cycle (depending on the exposure time). The mass change in the first cycle was 0.0244g at 15 seconds, 0.0468g at 30 seconds, and -0.0046g at 45 seconds. The total mass change in the third cycle was +0.0474g at 15 seconds, +0.072g at 30 seconds, and -0.0405g at 45 seconds. | FDM, smoothed with steam 'Final touch smoothing station' Stratasys (200-240 Volts AC, 50/60 Hz, 20 amp, MicroCare SSF Smoothing Station Fluid) | Uprint-SE | ABS-P400, MicroCare SSF Smoothing Station Fluid MCC-SSF01P (fluido Decafluoropentane (10-30%), Trans-Dichloroethylene (60-100%)) | Roughness Ra, mass | Print orientation, exposure time, cycle number | Print orientation: 0, 90°, exposure time: 15, 30, 45 sec; cycle number: 1, 2, 3 | The best roughness improvement result in the first cycle is obtained by using 45 seconds of exposure, with an improvement of 94.33% (Ra roughness goes from 9.059+/-0.015 um to 0.513+/-0.0136um). The use of two additional cycles improves the final roughness by 97.72% (Ra 0.206+/-0.0114um), meaning that most of the improvement is achieved in the first cycle. For the first cycle at 45 seconds, the mass is reduced by -0.0046gr, which is 0.077%. For the three cycles, the total mass loss is 0.6769%. For a cycle time of 15 seconds, the piece expands at the end of the three cycles, gaining 0.0474gr or 0.7965%. And for 30 seconds, it gains 0.0728gr or 1.2% of the original mass. | Finishing Touch Smoothing Station, 200-240 Volts AC, 50/60 Hz, 20 amp a $30000USD (https://www.fabbaloo.com/blog/2013/5/28/hands-on-with-the-finishingtouch-smoothing-station-html consultado marzo a abril de 2021), MicroCare SSF Smoothing Station Fluid MCC-SSF01P x 19 Lt a $742USD. *Las maquinas requieren consumo de recursos enenrgeticos y consumibles para su operacion. *Algunas operaciones requieren el uso de ventilacion y elementos de proteccion personal que incrementan los costos (fluido Decafluoropentane (10-30%), Trans-Dichloroethylene (60-100%)) (https://www.microcare.com/en-US/Products/MicroCare-SSF-Smoothing-Station-Fluid consultado marzo a abril de 2021) |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness, tolerances and fits. | Chemical attack, experimental characterization | S3 | Study the influence of FDM parameters on the surface finish of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) prototypes subjected to chemical attack by liquid acetone. | In the first phase, which consists of specimen manufacturing, the variables considered are the tip size, the frame width, and the slice height. Square base prisms of 18 X 18 X 8 mm have been manufactured using different levels of the input variables. The tip values were 0.254 mm (low) and 0.305 mm (high), the frame width was 0.305 mm (low) and 0.709 mm (high), and the slice height was 0.178 mm (low) and 0.254 mm (high). In the second phase of the experimentation, the specimens were subjected to a chemical finishing process. The process involved immersion in a volume of 90% dimethyl ketone and 10% water for 300 s. All sample sizes were measured before and after chemical finishing to evaluate any variations. | In the first experimental phase, it has been shown that the Ra Roughness on the lateral surface (average around 20um) does not depend on the tip dimension and raster. There are improvements in roughness from 30μm to 10μm on the upper surface, that is, a reduction or improvement of 66.6% in roughness, with layer height and width parameters of 0.254mm and 0.729mm changed to 0.178mm and 0.305mm. In the second experimental phase, the specimens were reduced by less than 1%, while their average weight increased by less than 1%, considering an initial average weight of 2.5g per specimen. The samples dramatically improved their finish, the group with the lowest average roughness of 11.8um on the top and 16.2um on the side after treatment achieved roughness of 2.2um and 5.1um on the top and side, respectively, which was an improvement of 81.35% and 68.51%, and the group with higher roughness on the top of 17.2um and 18.8um improved by 4.6um and 8.7um or 73.25% and 53.72%, respectively, and the results were applied in the production of an artwork. The bounding box of the prototype measures 34 x 24 x 62 mm. The prototype was immersed in the chemical bath and its roughness was measured in a 5 x 5 mm area considered on the back. From an average roughness Ra equal to 28.5 μm, the roughness was reduced to 11.5 μm, that is, there was a reduction or improvement of 59.6% compared to the original value for a layer height of 0.254mm and a raster width of 0.729mm. | FDM, liquid dimethyl ketone | not specified | ABS | Roughness (Ra) top and side, dimensional tolerances. | nozzle size (d), layer height (t), weft width (b), chemical treatment, type of test specimen Please note that I have removed the quotation and double quotation marks from the translated value as requested. | d: 0.254 mm, 0.305 mm, b: 0.305 mm, 0.709 mm t: 0.178 mm, 0.254 mm; chemical treatment: immerse in 90% acetone for 300 s; type of piece: test specimens and statue | The best result of roughness by changing printing parameters is achieved by reducing the layer height and line width (from 0.254mm and 0.729mm to 0.178mm and 0.305mm) for the top surface of the part, reducing the roughness from 30μm to 10μm, which is a reduction or improvement of 66.6% in roughness. The roughness on the side surface does not depend on the nozzle or line width and remained at 20um. Changes in roughness by immersing specimens in 90% acetone (10% water) for 300s improved the top surface by 73-81% (from 11.8, 17.2um to 2.2, 4.6um), the side surface by 53-68% (from 16.2, 18.8um to 5.1, 8.7um), and transferring the manufacturing parameters to an artistic piece achieved a 40% improvement in finish (from 28.5 to 8.5um). | Pure anhydrous acetone x 250ml at $8-10USD, pure acetone (nail polish remover) x 473ml at $10usd. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs. |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness | Machining, Deformation | S5 | The objective of this work is to develop a geometric model of the deposited filament to predict the surface roughness of the part after the barrel finishing (BF) operation. | Specimens with suitable geometry have been designed to reverse the different deposition angles. They are composed of five cubes with a lateral length of 15 mm, rotated by 18°: this provides surface slopes ranging from 0° to 180°. The virtual model has been developed in Mathematica 9.01. For manufacturing, a Stratasys Dimension BST 768 printer has been used with solid model filling and two layer thicknesses of 0.254 mm and 0.331 mm. The material used for manufacturing has been acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). The BF operation was performed by a ROTAR EMI industrial mill with a loading capacity of 47 liters. The media used were small ureic conical elements with a diameter and height of 10 mm. The barrel has been filled in a range between 30% and 60% with a 10% increment. The rotation speed has been continuously varied through an electronic motor controller from 0 to 140 rpm. The range of rolling and cascading movements is contained within the range of 20 rpm to 50.5 rpm. The experimental load has consisted of 24 kg of abrasive media. The specimens have been machined for 960 min and measured at specified working times. Three acquisitions have been made for each set of parameters (deposition angle, layer thickness, and working time). | The original surface was significantly flattened by the operation, highlighting a strong reduction in peak height to valley height. A regularization of the surface can also be observed: the original surface has peak heights ranging from 0.04 mm to 0.11 mm, while for the machined surface, peak heights vary between 0.01 mm and 0.05 mm, resulting in a 75%-55% reduction in height roughness for layers of 0.254 mm and 0.331 mm, as well as angles from 0 to 180°, with a post-processing time of 800 minutes. The depths of the valleys show a variability of less than 8% both before and after the operation, confirming the applicability of the method. In the case of the vertical wall, the variability at the top of the peak is approximately 7% of the total height, but after 8 hours of machining time, it has been significantly reduced to less than 1%. At a deposition angle of 90°, a value of 5 μm is reached after 8 hours of working time, corresponding to a 75% decrease. For other deposition angles, the descent speeds are lower. The maximum lateral deformation is insignificant in the first stage of the BF operation and occurs as the sides are more exposed to the action of the medium, as confirmed by the R-squared value, which indicates that the predictor explains 91.4% of the variance in RM. In the first stage, up to 120 minutes, the model overestimates the experimental data. The Ra model underestimates the experimental data up to 240 minutes due to the observed RM deviation. Validation shows very good agreement, as indicated by the R-squared and adjusted R-squared values exceeding 86%, although the model is less suitable in the mentioned first stage. The residuals are less than 0.5 μm and around 1 μm at working times of 480 and 960 minutes, respectively, confirming the reliability of the model. | FDM, BORED (mill with ureic conical elements) | DimensionBST 768 | ABS | Roughness Ra, Rq, Rt, Rsk, Rku, delta a, delta q | Print orientation (OI), mill filling percentage (%), mill rotation speed (rpm), drilling time (tb) | OI: 0-180° (from 18° to 18°); %:30-60 (from 10 to 10); rpm: 0-140; tb: 0-960min | The original surface was noticeably flattened, with peak heights ranging from 0.04 mm to 0.11 mm, while for the machined surface, peak heights vary between 0.01 mm and 0.05 mm, resulting in a 75%-55% reduction in roughness height for layers of 0.254 mm and 0.331 mm, as well as angles from 0 to 180°, with a post-processing time of 800 minutes. A surface regularization was observed, with valley depths showing a variability of less than 8% both before and after the operation. In the case of the vertical wall, the variability at the top of the peak is approximately 7% of the total height, which is significantly reduced after 8 hours of machining, reaching less than 1%. The maximum lateral deformation is insignificant in the first stage of the operation at 120 minutes of BF and occurs as the sides are more exposed to the action of the medium. When using a theoretical model to predict roughness data in the first stage, up to 120 minutes, the model overestimates the experimental data, and up to 240 minutes, the Ra model underestimates the experimental data. Validation shows very good agreement with residuals less than 0.5 μm and around 1 μm for working times of 480 and 960 minutes, respectively. | Rotary drum with a capacity of 3.3 liters (317.5mm length x 241.3mm diameter, approximate measurements), at $112USD. Rotary drum with a capacity of 7 liters (381mm length x 279.4mm diameter, approximate measurements), at $190USD. 5 lb bag of abrasive media made of stainless steel cylinders, with a diameter of 1.2mm x length of 6.47mm, at $42.95USD. *Machines require energy resources and consumables for operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment, which increase costs. |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness | Machining | S6 | The objective of this work is to develop a methodology capable of unlocking the possibility of finishing the modeling pieces of fused deposition by computer numerical control machining. | The virtual model, used to manufacture the physical FDM prototype, is analyzed to calculate the dimensional deviation from the nominal value and to evaluate the cutting depth based on the deposition angle. The dimensional deviation has been modeled based on the deposition angle. This expression allows determining the actual position of a surface produced by FDM. In this way, it is possible to provide the CNC CAM with the real geometry as the starting material. The virtual model used in this analysis is an STL file. For each facet, the deposition angle can be calculated. This angle is necessary to determine the dimensional deviation and the cutting depth. The final model can be obtained by subtracting the cutting depth from the physical prototype, which has dimensional values equal to the nominal value plus the deviation introduced by the technology. The geometry of the specimen is a square parallelepiped measuring 20x20x10 mm. They have been manufactured with seven different inclinations to obtain surfaces characterized by the deposition angles 0°, 3°, 9°, 15°, 30°, 60°, 90°. For the manufacturing, a Stratasys Bst 768 has been used, employing ABS-P400 material. The chosen manufacturing parameters have been: 0.254 mm layer thickness, solid model filling, and support generation method. The obtained pieces have been machined by a 3-axis CNC milling system equipped with a 24,000 rpm ELTE spindle. A 6 mm diameter Gühring solid carbide end mill has been used. According to the manufacturer and calculating the compromised effective diameter, the cutting speed ranged from 2.6 to 6 m/s within the optimal range for thermoplastic material. The feed rate and transverse feed rate have been set at 0.05 mm/rev and 0.25 mm respectively. Ten cutting depths have been investigated, ranging from 0.05 mm to 0.5 mm with a step of 0.05 mm. All the obtained data has been structured to obtain the contour plot of Ra as a function of the cutting depth and the deposition angle. A multi-objective optimization has been used. For each deposition angle, a function relating the achievable roughness R with the cutting depth p has been found through a polynomial interpolation fit. The proposed methodology has been applied to a Pelton wheel cube, a surface characterized by all deposition angles belonging to the range 0-90°. Only half of the cube has been finished to compare with the other half without machining. The cube prototype has been manufactured by a Stratasys Dimension Bst 768 using ABS P-400 and choosing the same process parameters as in the previous experimentation. | The morphology of the surface is strongly affected by the deposition angle. The surface morphology changes significantly with its slope: this requires different machining conditions for a prototype characterized by surfaces with different slopes. Adequate choice of the cutting depth is needed. An experiment has been designed to determine the cutting depth as a function of the deposition angle that minimizes roughness. The obtained formulation has been integrated into a methodology that, starting from the original STL file used for FDM manufacturing, allows obtaining the modified virtual model that provides the CNC CAM with a variable cutting depth. The method has been applied to some surfaces of a functional prototype, which has yielded very good results. For example, in the experimental stage at a 60° angle, the chosen cutting depth is 0.1 mm, a marked reduction in peak height is observed, but the original valleys are not eliminated. In this case, the initial average roughness is 17 μm and, after finishing, it becomes 2.5 μm, which is a reduction or improvement of 85.3%, and with a slight increase in depth, this result is improved. The specimen manufactured with a deposition angle of 60° shows a very low initial roughness. By setting the cutting depth to 0.05 mm, a roughness of about 4 μm Ra can be obtained. A very good result has been obtained at a cutting depth of 0.15 mm, where the average roughness shows a minimum value of 0.97 μm with a standard deviation of 0.022 mm. For validation, some roughness measurements have been made in the indicated areas. Zone A is characterized by a slight curvature with an average deposition angle of 0°. The initial roughness is higher than 20 μm, as expected, and is reduced to 1.83 μm (a roughness reduction of 90.85%). The function that minimizes roughness as a function of the deposition angle and cutting depth keeps the roughness below 2 μm. | FDM, CNC milling | Bst 768 | ABS-P400 | Surface roughness Ra | Print orientation (PO), cutting speed (CS), cutting depth (cd) | OI: 0°, 3°, 9°, 15°, 30°, 60°, 90°; VC: 2,6 and 6 m/s; tc: 0.05 mm to 0.5 mm with a step of 0.05 mm. | *Different machining conditions are required for a prototype characterized by surfaces with different slopes. *The ideal cutting depth depends on the deposition angle to achieve roughness values around and below 2um. In some cases, this represents specific improvements of 85.3% (at 60° and 0.1mm depth, going from 17 μm to 2.5 μm) in the test specimen and higher (a minimum value of 0.97 μm at 60° and 0.15mm depth), or 90.85% in the wheel cube (from 20 μm at 0° to 1.83 μm). *The use of the methodology increases planning and file preparation times, in addition to machining times. | CNC milling/engraving machine at $290-370USD, set of 10 1/4' carbide bits at $47USD. *The machines require energy resources and consumables for their operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs. |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness | Machining | S7 | A semi-empirical model is presented for evaluating the surface roughness of a layered manufactured part using the modeling of the melt deposition, and an attempt is made to solve the staircase effect problem using a simple material removal method, namely, hot cutting machining (HCM). | The ABS FDM part is manufactured with a layer thickness of 0.254 mm, a model temperature of 270 °C, a support structure temperature of 265 °C, a road width of 0.511 mm, and zero air gap to carry out the surface roughness study. The designed part has four faces, which are inclined at 10°, 15°, 30°, and 45°, respectively, with the vertical. A simple semi-empirical model is developed by approximating the layer edge with a parabola with a base length of t/cosϴ and a height of 30-35% of the base length, where t is the layer thickness and ϴ is the construction orientation. Using the method of mean central line (Ra) surface roughness evaluation, the Ra value is obtained as the comparison of the surface roughness obtained by the experiments. A fractional factorial design of experiments with two levels and four process variables is applied to understand the effect of three important machining parameters, namely, the milling cutter inclination angle (40° to 60°), cutting speed (15 to 30 m/min), and cutting direction with respect to the layers (0° to 90°). In addition to the aforementioned machining parameters, the construction orientation (10° to 45°). | The proposed machining method is capable of producing a surface of the order of 0.3 μm with a confidence level of 87%. The developed statistical model is capable of predicting the surface roughness after HCM with a correlation of over 99% and a confidence level of 97% in the machining direction. This machining process provides a key to the development of a hybrid rapid prototyping system, which will have machining and layer deposition characteristics simultaneously, in order to achieve. | hot machining | not specified | ABS | Surface roughness Ra | Print orientation (PO); milling cutter inclination (MC); cutting speed (CS); cutting direction with respect to the layers (CD) | IF: 40° to 60°, VC 15 to 30 m/min; DC: 0° to 90°; OI: 10° to 45 | The proposed machining method is capable of producing a surface of the order of 0.3 μm with a confidence level of 87%. | Hot machining: CNC milling/engraving machine at $290-370USD, set of 10 1/4' carbide bits at $47USD, soldering iron at $20USD. Machines require energy resources and consumables for operation. Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs. |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness, tolerances and fits. | Machining, Deformation | S9 | study the integration between this technology and the barrel finishing operation (BF) to improve the surface quality of the piece. | A geometric model of the profile under machining is proposed. The model takes into account the FDM formulation and allows predicting the morphology of the surface achievable by BF. The necessary RM in the model is obtained through a particular profilometer methodology, based on the alignment of Firestone-Abbot (F-A) curves. The experiment carried out on a suitable geometric model validated the geometry. Profilometer and dimensional measurements have been used to evaluate the result of the coupled technologies in terms of surface roughness and accuracy. | The deposition angle strongly affects the BF removal rate and alters the nominal dimensions of the part. The height forecast allows estimating the BF working time to meet the part requirements. The forecast of the surface that can be obtained through this integration is a tool to find the optimal orientation of the part to meet the drawing requirements. Profilometer measurements showed different roughnesses that decrease with the corresponding BF working time for different surface slopes. Those surfaces that have strict requirements should be oriented towards vertical walls characterized by lower surface roughness and faster BF improvements than others. BF machining modifies the deviation from the nominal value in a way that depends on the initial morphology of the FDM surface, that is, on its deposition angle. | FDM, BORED | Dimension BST 768 | ABS | Roughness Ra, dimensional deviation, removed area | Print orientation (PO), drilling time (dt) | OI: 0 to 180 from 18° to 18°; tb: 0, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480, 960min | The angle of deposition strongly affects the BF removal rate and alters the nominal dimensions of the piece. The forecast of the height allows estimating the BF working time to meet the requirements of the piece. Different roughnesses decrease with the corresponding BF working time for different surface slopes. Those surfaces that have strict requirements should be oriented towards vertical walls characterized by lower surface roughness and faster BF improvements than others. | Rotary drum with a capacity of 3.3 liters (317.5mm length x 241.3mm diameter, approximate measurements), at $112USD. Rotary drum with a capacity of 7 liters (381mm length x 279.4mm diameter, approximate measurements), at $190USD. 5 lb bag of abrasive media made of stainless steel cylinders, with a diameter of 1.2mm x length of 6.47mm, at $42.95USD. *Machines require energy resources and consumables for operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment, which increase costs. |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness, tolerances and fits. | Chemical attack, experimental characterization | S10 | Make an effort to investigate the effect of the parameters of the fused deposition modeling (FDM) process on the surface finish of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) replicas (as a preprocessing stage), followed by the chemical vapor smoothing (CVS) process (as a post-processing stage) as a case study. | In this work, a biomedical implant has been selected (hip joint with estimated measurements of 18mm diameter x 360mm length). The selected 3D component has been modeled in the Y-Z plane of SolidWorks software and then converted to .STL format. This research work has been divided into two stages. In the first stage (preprocessing stage), ABS material samples were fabricated on the FDM machine (uPrint -SE® by Stratasys Inc.) by varying the orientation (0° and 90°) and the density of the part (high, low, and solid interior style with manufacturing time and material of 35 min and 0.96cm^3 for 0°, 17 min and 0.86cm^3 for 90°). In the second stage, the CVS process was carried out on the Finishing Touch smoothing station (brand: Stratasys Inc.). The various influencing factors, their levels, and the interaction between the factors were decided based on an extensive literature review and pilot experimentation (orientation from 0 to 90°; high, low, and solid density; cycles 3, 4, and 5; time 4, 6, and 8 seconds). | From the results of Stage 1, it has been observed that the specimen manufactured with a 90° orientation and a solid interior has a better surface finish (lower Ra) compared to any other specimen (at 90° and solid density, the roughness is 5.006μm, the highest roughness is for 0° and high density with a roughness of 8.742μm, which is up to 57.3% of the value at 90° or a reduction of 42.7%). The result of Stage 2 indicates that the surface finish of the prototypes has improved dramatically after the application of CVS (the roughness varies between 0.144μm for 90° and solid density with 3 cycles of 6 seconds, and 0.241μm for 0° and high density with 5 cycles of 4 seconds, with the highest roughness value after CVS of 0.447μm for 0° orientation and low density with 5 cycles of 6 seconds when before the roughness was 8.320μm, that is, percentage-wise, 2.9%, 2.8%, 5.4% of the original roughness values or reductions of 94-97% of the original roughness). The surface finish of all prototypes manufactured after CVS has become almost the same (statistically, none of them has been significant at the 95% confidence level). The effect of certain parameters of the FDM and CVS process on dimensional accuracy has also been analyzed. For one of the dimensions (6 mm), a positive deviation from the drawing dimension has been observed for the selected dimension after the manufacture of the prototypes using the FDM process. The CVS process slightly reduces the selected dimension. As the selected dimension is reduced after the CVS process, the process is beneficial in this case as it reduces the overall deviation between the drawing dimension and the finished prototypes (deviation after printing for 90° and solid density is 0.71%, for 0° and high density is 0.68%, after CVS it ranges from 0.4% to 0.48%). To obtain the conditions that result in an optimal surface finish with the lowest cost (in terms of support material and chemical used), effort, and time, the input parameters for the optimal surface finish are 90° orientation, solid piece density, three cycles, and 6 s cycle time. Two confirmation tests were performed with the optimal values of the factors. The Ra values before and after CVS were 5,005 and 0.158 μm, and 5,062 and 0.152 μm, respectively (improvement or reduction in roughness of 96.8% and 96.9%). | FDM, acetone vapor (Finishing Touch smoothing station) | uPrint -SE | ABS | Roughness Ra, dimensional deviation or dimensional tolerance. | Printing orientation (OI); piece density (%); treatment type; treatment cycles and time. | OI: 0° and 90°; %: high, medium, low; treatment type: smoothing station; cycles 3, 4 and 5; time 4, 6 and 8 seconds | *It has been observed that the specimen manufactured with a 90° orientation and a solid interior has a better surface finish (lower Ra) compared to any other specimen (at 90° and solid density, the roughness is 5.006μm, the highest roughness is for 0° and high density with a roughness of 8.742μm, that is a reduction of 42.7%). *The surface finish of the prototypes has improved dramatically after the application of CVS (the roughness varies between 0.144μm and 0.447μm, in summary, percentage-wise, it represents reductions of 94-97% of the original roughness). *The surface finish of all prototypes manufactured after CVS has become almost the same (statistically, none of the process parameters has been significant at the 95% confidence level). *A positive deviation from the drawing dimension has been observed for the selected dimension after the manufacturing of the prototypes using the FDM process, as CVS slightly reduces the selected dimension, the process is beneficial in this case (deviation ranges from 0.68% to 0.71% when printing, and from 0.4% to 0.48% after CVS). *The input parameters for optimal surface finish (with the lowest cost in terms of support material and chemical used) are 90° orientation, solid piece density, three cycles, and 6 s cycle time (Ra values before and after CVS were 5,005 and 0.158 μm, and 5,062 and 0.152 μm, respectively, representing an improvement or reduction in roughness of 96.8% and 96.9%). | Finishing Touch Smoothing Station, 200-240 Volts AC, 50/60 Hz, 20 amp at $30000USD (https://www.fabbaloo.com/blog/2013/5/28/hands-on-with-the-finishingtouch-smoothing-station-html consulted March to April 2021), Pure anhydrous acetone x 250ml at $8-10USD, pure acetone (nail polish remover) x 473ml at $10usd. *Machines require energy resources and consumables for operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs. |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness, mechanical resistance. | Chemical attack, experimental characterization | S14 | Provide a universal finishing method or solution for FDM parts made of PLA, and represent the evolution of surface topography between adjacent layers during chemical finishing operation by constructing a geometric model of the deposited filament. | The raw material of the filament is PLA, which easily dissolves in some organic solvent, such as dichloromethane. The tensile properties are determined according to ISO 527:2007 standard (failure area of 4mm thickness and 10mm width, total length of 180mm). The specimens for the experiment were fabricated using a desktop 3D printer. The extrusion temperature was 175°C, while the extrusion speed was maintained at 30 mm/s. The specimens were built in the X and Y directions (horizontal and vertical) with a 20% infill. The built parts were subjected to a chemical treatment process by exposing them to dichloromethane vapors (99% concentration). For the vapor treatment, the part was kept inside a sealed glass bottle filled with 30 mL of dichloromethane, and the part was hung from the top. Finally, the optimized treatment time was 30 minutes. According to the aforementioned standard, the test speed was set at 2 mm/min, and the specimens were loaded until they broke. The maximum possible load of the specimens was 2.5 kN. | The tension resistance is reduced by 63% and the elongations at break improve by 50%. The results highlight that most of the deviations between the measured and calculated values are within 5 μm. The average tensile force before chemical finishing is indicated as F.X = 1,004 kN and F.Y = 1,100 kN. The tensile force of the specimens constructed in the Y direction is almost the same as in the X direction. After chemical finishing, the maximum tensile force decreased to 0.3853 kN (for the X direction) and 0.4638 kN (for the Y direction). The resistance values are 27 MPa for tensile strength at the yield point and 2.4% for elongation at break, resulting in a reduction of tensile strength to 10 MPa and elongations at break reaching 3.6%. | FFF, dichloromethane vapors (99% concentration). | not specified | PLA, diclorometano | Resistance to tension, roughness Ra | Print orientation (OI), amount of dichloromethane and exposure time. | OI: horizontal edge; quantity: 30ml at 99% for 30 minutes | The tension resistance is reduced by 63% and the elongations at break improve by 50%. The results highlight that most of the deviations between the measured and calculated values are within 5 μm. | Data: Diclorometano x 4L a $15-17USD (consultado en mercado libre colombia abril de 2021), Diclorometano Baker x 4L a $65-67USD (consultado en mercado libre colombia abril de 2021), Dichloromethane x 4L at $15-17USD (consulted on mercado libre colombia April 2021), Dichloromethane Baker x 4L at $65-67USD (consulted on mercado libre colombia April 2021) Note: The translated value has been provided without any quotation or double quotation marks at the start or end. |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness | coating | S15 | In this study, nickel has been considered as the coating material to achieve better mechanical and electrical properties, weight reduction, and cost savings. It is necessary to manufacture ABS parts by FDM and metallize the surface. | To study the roughness of the surface and the thickness of the coating of ABS M30 plated parts, specimens are manufactured using the Fortus 250 mc (Stratsys Inc.) FDM machine. The parts specifications are 30X20X5 mm. The established parameters are the raster angle (0°, 45°, and 90°) and the air gap (0, .05, and 0.1mm). The substrates have been pre-treated with graphite powder (50 mesh), followed by smoothing the surface with the help of sandpaper (dry grain size 1000). Coating parameters such as voltage (6, 9, and 12 volts) and metallization time (10, 15, and 20 minutes) are also considered in a controlled environment. A electroplating equipment consists of a direct current power source, a standard electrolyte solution, a cathode (graphitized samples), an anode (Ni metal), and a vessel or container to contain the solution. The electrolytic solution in appropriate quantity in one liter of distilled water: NiSO4 (275 g/L), NiCl2 (55 g/L); H3BO3 (45 g/L); Brightener spectrum 77 (0.3 mL/L); Ni additive 22 (3 mL/L), 55-60 °C. | After galvanizing, the roughness is 1.36μm and Ni thickness is 34.07μm for a raster angle of 90°, air gap of 0, 12 volts, galvanizing time of 15 minutes, and a roughness of 2.11μm and Ni thickness of 38.24μm for a raster angle of 0°, air gap of 0.1mm, 6 volts, galvanizing time of 5 minutes. The parameters that minimize the roughness to 1.295μm are galvanizing time of 12.5 minutes, 11.557 volts, air gap of 0.002mm, raster angle of 5.047°. Time is not a significant parameter, but its interaction with other parameters is. With an increase in the value of the raster angle and air gap, the roughness of the surface of nickel-plated FDM construction parts increases significantly. It is evident that the raster angle with voltage has less effect on the surface roughness. Similarly, with an increase in the raster angle, the surface roughness increases, and the decrease in surface roughness with voltage increases. | plated nickel | Fortus 250 mc | ABS M30 | Roughness Ra, nickel plating thickness | voltage metallization time the angle of the pattern, the air gap | Voltage (6, 9, and 12 volts) and metallization time (10, 15, and 20 minutes), the screen angle (0°, 45°, and 90°), and the air gap (0, 0.05, and 0.1mm). | After galvanizing, the roughness ranges from 1.36um to 2.11um with layer thicknesses ranging from 32.07um to 61.65um. Time is not a significant parameter, but its interaction with other parameters is. With an increase in the value of the raster angle and the air gap, the roughness of the surface of nickel-plated FDM construction parts increases significantly. It is evident that the raster angle with voltage has less effect on the surface roughness. With an increase in the raster angle, the surface roughness increases, and the decrease in surface roughness with voltage increases. | Data: Adhesive element graphite powder mesh 50 x 1 kg at $150usd (consulted on Amazon in April 2021), Nickel Tape 0.15x6x50mm x 50 units at $6USD, roll of nickel tape 0.2x8mmx9.75m at 17USD, cable with 50cm alligator clips, 20AWG at 8A x 10 units at $25USD or cable with 50cm alligator clips 22AWG x 5 units at $7USD, Water or Distilled Water, adjustable power supply 110/120V input to 0-30V output/0-10A at $70USD or power supply 120V input to 0-15V output/0-2A at $45-50USD, nickel sulfate (NiSO4) x 1kg at $5USD (consulted on Alibaba in April 2021), nickel chloride (NiCl2) x 1kg at 3.7USD (consulted on Alibaba in April 2021), boric acid (H3BO3) x 1lb at 5-13USD (consulted on Alibaba and Amazon in April 2021), Brightener spectra 77 x 1kg at 20USD (consulted on Alibaba in April 2021), 250ml beaker glass at $5-8usd, 1000ml beaker glass at 14usd, inconel 625 powder alloy (nickel additive 22) x 1kg at 100USD (consulted on Alibaba in April 2021), set of glass precipitate beakers of 50,100 and 250ml at $11USD, kit of beaker glass of 100, 250, 500, 1000ml at $20-30usd. *Machines require energy resources and consumables for their operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs. Adhesive element graphite powder mesh 50 x 1 kg at $150usd (consulted on Amazon in April 2021), Nickel Tape 0.15x6x50mm x 50 units at $6USD, roll of nickel tape 0.2x8mmx9.75m at 17USD, cable with 50cm alligator clips, 20AWG at 8A x 10 units at $25USD or cable with 50cm alligator clips 22AWG x 5 units at $7USD, Water or Distilled Water, adjustable power supply 110/120V input to 0-30V output/0-10A at $70USD or power supply 120V input to 0-15V output/0-2A at $45-50USD, nickel sulfate (NiSO4) x 1kg at $5USD (consulted on Alibaba in April 2021), nickel chloride (NiCl2) x 1kg at 3.7USD (consulted on Alibaba in April 2021), boric acid (H3BO3) x 1lb at 5-13USD (consulted on Alibaba and Amazon in April 2021), Brightener spectra 77 x 1kg at 20USD (consulted on Alibaba in April 2021), 250ml beaker glass at $5-8usd, 1000ml beaker glass at 14usd, inconel 625 powder alloy (nickel additive 22) x 1kg at 100USD (consulted on Alibaba in April 2021), set of glass precipitate beakers of 50,100 and 250ml at $11USD, kit of beaker glass of 100, 250, 500, 1000ml at $20-30usd. *Machines require energy resources and consumables for their operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs. |

| G1, G6 | Finished or surface roughness, tolerances and fits, mechanical strength | coating, coating/infiltration, chemical attack | F61 | In this study, some practical approaches are addressed to ensure surface roughness and tightness, such as shrinkage testing, leak testing, and tensile strength testing of the sample after further processing with acetone immersion, acetone vapor smoothing or fumigation, and epoxy resin infiltration. | The immersion/fumigation method in solvent is a method to improve the surface roughness according to the exposure time of the piece. ABS plus is used in ivory, with a layer thickness of 0.178 [mm], SR-30 soluble support material, maximum piece size of 127×127×127 [cm], manufactured in Stratasys Mojo TM printer, immersed in 99.5% acetone, maintained at 58°C (±1°C). In the fumigation method, a 500ml container filled with acetone up to 150ml is used, while in the immersion case, a 500ml container filled with acetone up to 300ml is used. The resin infiltration is done as follows: mix the resin with a magnetic stirrer to remove bubbles, the parts to be post-processed are immersed in the resin in the vacuum chamber, vacuum is used to infiltrate the resin. Remove the rest of the useless resin and perform post-curing. The resins used in the study were YD-115J liquid epoxy (Kukdo chemicals Co., Ltd.) and Tetraethylenepentamine epoxy curing agents (Dow Chemical Co.) with a weight ratio of 100 to 13. The comparison resin mixed with a diluent is prepared. The diluent used was Methyl Ethyl Ketone (MEK), mixed with the comparison resin (at 0%, 5%, and 10% by weight of the total weight). Standard ASTM-D638 tensile samples (type 5: 2mm thickness, 63mm length, 9.53mm width at the ends, and 3.18mm at the failure zone) are selected. A 10mm cubic 3-D model of the specimen is used in the shrinkage test. The chemical post-processing time is 10, 20, and 30 seconds. The tightness measurement of the parts manufactured by FDM was performed on elbows with different angles (45°, 90°, and 135°) manufactured lying down. An additional test is performed on the collector to apply the vacuum measurement device used for the tightness test and confirm the possibilities of using the post-processed piece based on the results of the previous experiment. | The maximum load of the untreated specimen is 246.47 [N]. The post-processing times for the fumigation method and the immersion method are 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 seconds. Chemically post-processed specimens have a lower maximum load value than the base specimen (maximum value is approximately 240N and 230N for the fumigation and immersion methods respectively for a time of 5 seconds, and the smallest maximum load is approximately 210N for both methods and a time of 20 to 30 seconds, which is a reduction in strength to a value relative to the original of 97.4%-93.31% to 85.2%-84%, or a reduction of 2.6%-6.9% to 14.8%-16%). For the resin infiltration method, the maximum load ranged from 265N for 10wt% to 285N for 0 to 5%wt (this is 116%-107%, meaning an increase of 16%-7%). The shrinkage ratio decreases as the MEK content increases in the post-processed specimens using the resin infiltration method. This is because as the amount of MEK increases, the thickness of the resin coated on the surface of the specimens decreases (quantitative results show that the fumigation method has a distortion of -0.25% for 10 seconds, and the smallest distortion is approximately 0% for 20 seconds, while the immersion method has a maximum distortion of -0.20% for 30 seconds, and the smallest distortion of -0.15%, the proposed infiltration method has the largest distortion among the three methods, for 0wt% the distortion is -0.45% and the smallest is -0.10% for 10wt%). The results of the leak test (holding a vacuum pressure or negative pressure for a longer time) for the fumigation method showed that the 135° elbow achieved tightness for almost the same time as the untreated elbow, around 40 seconds (the pressure for the untreated sample was -60kPa and for the treated sample was -90kPa), but the pressure rise was not as sudden as in the untreated elbow (not all the surface reacted to the acetone vapor). For the infiltration and immersion methods, favorable results are obtained by holding negative pressure (-50kPa to -90kPa for immersion, which is 180% or an increase in absolute pressure of 80%, -40kPa to -90kPa, which is 225% or a percentage increase in absolute pressure of 125%) during the test (340 seconds). Similar results were achieved for the infiltration method at 10wt% in a complete device. | FDM, vacuum chamber | Mojo TM | ABS plus | Maximum load to tension resistance, contraction, tightness, pressure, pressure time. | immersion time, fumigation time, infiltration time, diluent concentration in infiltration method | The post-processing times for the fumigation method and the immersion method are 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 seconds. Diluent concentration: 0%, 5%, and 10% by weight of the total weight. | *Chemically post-processed specimens have a lower maximum load value than the base specimen, with a reduction in strength ranging from 2.6% to 6.9% for 5 seconds to 14.8% to 16% for 20 to 30 seconds, with fumigation showing higher strength values than immersion. *The shrinkage ratio decreases as the solvent content increases in post-processed specimens using the resin infiltration method, and the thickness of the resin coated on the surface of the specimens decreases. *The shrinkage of the infiltration method (-0.45% to -0.10%) is greater than the other methods (fumigation -0.25% to 0%, immersion -0.20% to -0.15%). *The results of the tightness test for the fumigation method yielded similar results to the untreated elbow (the pressure for the untreated sample was -60kPa and for the treated sample was -90kPa for 40 seconds). For the infiltration and immersion methods, more favorable results are obtained by maintaining negative pressure (-50kPa to -90kPa for immersion, -40kPa to -90kPa for infiltration) during the 340-second test, achieving similar results for the infiltration method with 10% solvent. | Infiltration of resin: Liquid Epoxy Resin x80gr at $8-10USD, rigid epoxy resin (1:1 ratio) x 1000ml at $17-19usd, rigid epoxy resin (1:1 ratio) x 1kgx840ml at $14-16usd, epoxy resin xtc 3d (2:1 ratio) x 181ml x 181gr at $25USD, 3-gallon vacuum chamber kit x 137mm diameter x 111mm height x 1/4 hp power x 110v x 3.6 cfm x final vacuum 0.8pa at 180-240USD, Acetone (solvent reference). Fumigation and immersion: Anhydrous pure acetone x 250ml at $8-10USD, pure acetone (nail polish remover) x 473ml at $10usd, portable electric stove x 2000w x 110v at $18-20USD, portable gas stove at $30-32USD, *Machines require energy resources and consumables for their operation. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs. |

| G1 | Finished or surface roughness, tolerances and fits, mechanical strength | Chemical attack | S16 | To improve the surface finish of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS) FDM parts, a chemical treatment is performed in an acetone solution. The objective of this research is to investigate the influence of the chemical treatment on the FDM part used in terms of surface roughness, as well as strength. | In this project, ten ASTM D638 Type I standard specimens have been manufactured using the MOJO 3D printer (Stratasys). Five specimens of ABSplus material and SR-30 as support material through the print heads. The chemical solution is added with water with a volume of 90% dimethyl ketone and 10% water. The 5 specimens were immersed in the acetone solution for 300 seconds. All specimens were analyzed before and after being treated with chemicals. The test data includes Young's modulus (E), maximum force (Fmax), stress, and tensile strength. | The average surface roughness, Ra for the untreated specimen is 12.736µm while the treated one is 0.35µm (surface improvement of 97.25%). The tensile strength of the treated specimens has a lower resistance compared to the untreated specimens. The reduction in average tensile strength was 36,012MPa to 20,678MPa or 42.5% in percentage value. All treated specimens also have a lower modulus of elasticity compared to the untreated specimens. This means there are decreases in terms of stiffness after the piece is immersed in acetone. In terms of average reduction, the Young's Modulus has decreased from 6.5 to 4.96 GPA or 23.7% in percentage value. | FDM, liquid dimethyl ketone | MOJO | abs, abs+acetona | tension, rugosidad Language: English tension, roughness | Volumetric percentage, immersion time. | Water with a volume of 90% dimethyl ketone and 10%, for 300 seconds. | The average surface roughness is reduced by chemical attack, from 12.736µm to 0.35µm, which implies a surface improvement of 97.25%. The mechanical strength and elastic modulus are reduced compared to untreated parts, in the case of strength from 36,012MPa to 20,678MPa, a reduction of 42.5%, and the Young's modulus has decreased from 6.5 to 4.96 GPA, a reduction of 23.7%. | Pure anhydrous acetone x 250ml at $8-10USD, pure acetone (nail polish remover) x 473ml at $10usd. *Some operations require the use of ventilation and personal protective equipment that increase costs. |